Will My Grandmothers’ Stories Make It Into Rep. Maloney’s Women’s History Museum?

Can the women’s movement in America be summed up in a museum — or even in a word? Or is the idea of ‘feminism’ so contested right now that a bill to try to do this, will only spark debate?

Currently, Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY) garnered the support of more than half the House with 246 cosponsors to sign on to a bill to establish a National Museum of American Women’s History. That’s right. We don’t yet have one.

But as soon as we reported on that development in our political blog DailyClout.io, debate erupted. What would be in that museum? No one could agree. Would well-known women, most of whom are white and formally educated, predominate? What about everyone else who changed history? Would it tell of the many lost stories that men got credit for. Would gay women be included? What about trans women?

These questions drew me to the greater outlook on modern feminism. I think the debate about what feminism is today is healthy. As a twenty-something male who cares about this issue, my own closest personal connection to the history of feminism is through the lives of two women close to me who lived through most of recent US women’s history — my grandmothers.

But I wonder if these women’s lives will be reflected in this Museum. While their lives don’t mirror those of famous feminists — such as Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem. I wonder if my grandmother’s struggles , and many who endured as they did, will be reflected in this Museum.

My maternal grandmother, Marilyn, grew up in the American South and knew, even as a small girl, that there were certain things she could say and do — and others that she couldn’t. I recall her stories of mornings in the North Carolina heat: while she made her way walking to school — three miles in each direction — the white students, who passed her by while seated in comfort in their segregated school bus, would spit out the window onto her.

Both she and my grandfather recall going to watch movies in the cinema. They paid their nickel, just as everyone else did, but unlike everyone else who was white, they were forced to slink into an alleyway entrance, and sit in the balcony. The white customers sat up front and often threw popcorn and pop containers at the black customers in the balcony. “And that’s just how it was,” my grandmother told me.

She didn’t see anything wrong with it back then, and I imagine that is how she got through such an experience. Raised by her own grandmother, Marilyn made it through school, spent her life as an educator, and then instilled the importance of education in her own four daughters, including in my mother. To me this is a feminist life, though she would never use that term.

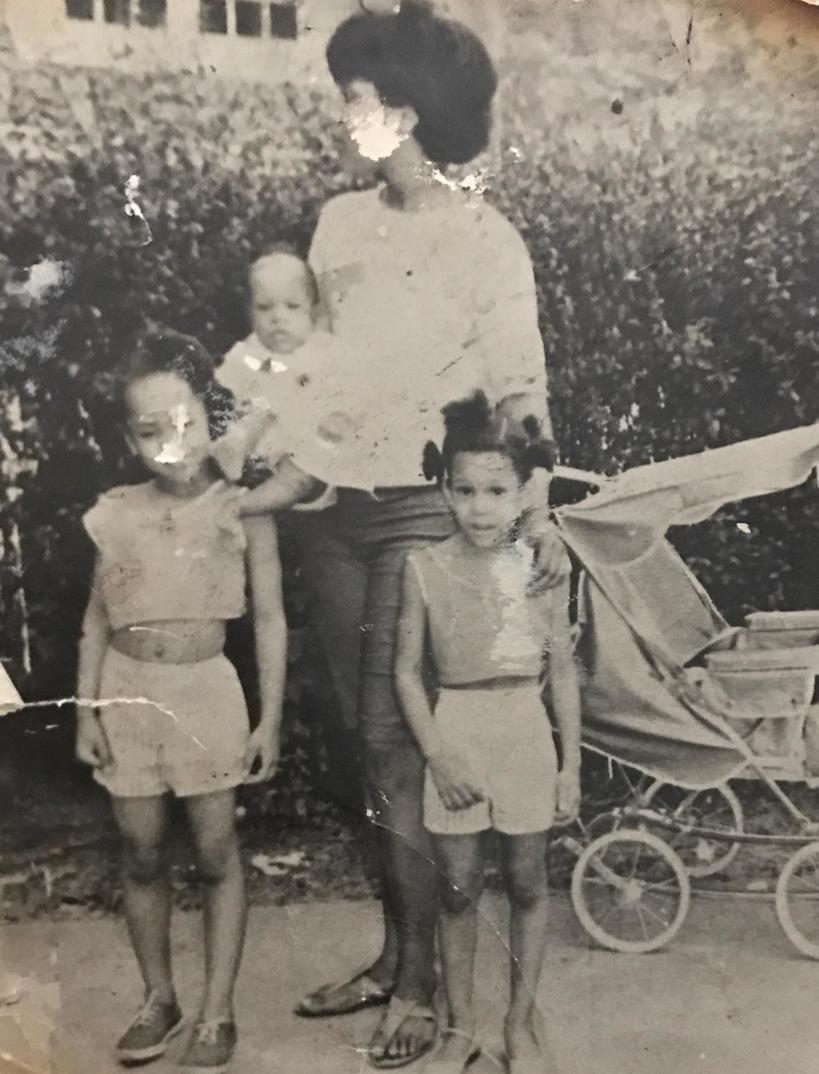

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, my paternal grandmother, Delores, was a first generation American who grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Her own mother came to this country from the West Indian Island, Saint-Kits & Nevis, to find a better life. Delores toiled in a Barry’s Biscuit Company factory as a young woman, preparing meal packages to support the war efforts of World War Two. This display of her work ethic and patriotism didn’t change the facts of life around her, as she raised a daughter of her own in a world where both women and blacks were seemingly never going to become more than second class citizens.

These scenes are what I think of when I hear the word ‘feminist.’ But that definition is in flux.

Indeed, the definition of ‘feminism’ has drastically changed from the movement’s early US origins in the 19th century. It’s been almost one hundred years since American women secured the right to vote.

Polling data reflects new changes in who identifies with ‘feminism’ and in what the word means. Today, 47% of the US public (and 60% of all US women) see themselves as ‘feminists’, according to a Washington Post and Kaiser-Family Poll. That percentage is six percent higher than it was twenty years ago — which is big news. The most enlightening result from the poll was the divergence between Millennials (women younger than 35) and their older feminist counterparts (that is, women older than 35). The Washington Post commented on what it calls New Wave Feminism: “Although millennial women, as a whole, view themselves largely as feminists — a logical notion, given their proximity to issues such as workplace equality and reproductive rights — their view of what it means to be a feminist is often far different than that of their mothers and grandmothers.”

The poll showed broad support for the goals of “empowerment” by millennials but less of an embrace of a rigid definition of ‘feminist’. If first-wave feminism focused mainly on suffrage and other legal rights, and second-wave feminism focused on bringing equality to the workplace and home, the New Wave of feminism seems to focus on bringing equality to the person — some would say to the ‘individual,’ a focus that Millennial women believe was missed earlier in the movement. (This critique may frustrate some older feminists, who make the case that you can only have individual equality when your legal equality is secure.)

While my grandmothers were not opposed to the feminist movement that grew in the 60’s, feminism had nothing much to say then about the racist laws they endured along with sexism. Delores was more worried about the safety of her sons and daughters, so much so that the words of Malcolm X eventually became very compelling to her. She would join the Nation of Islam and pick up the Muslim faith, a faith that is still present in my family today. Women’s movement leaders could not keep her and her family secure as race riots ripped through East Orange and Newark, New Jersey, where my Delores huddled with her children under her bed, as this was the only measure she could take to keep her children from flying bullets.

Now her life is less invisible in the New Wave of feminism. But there is further to go.

While the political movement that drove women out into the streets in the sixties is resurgent, as we saw with the Women’s March on Washington, it has grown wiser with age. There is a broader idea of feminism that moves digitally — through the internet, through activity on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. It lives amorphously in the minds of its followers, and really, it has no great individual leaders. Its tenets are written not in books or manifestos but in blogs, tweets, memes, emojis, and comments. And it includes some names feminists of the past would not have allowed in. Though incredibly diverse in their thinking, such women as Beyonce, Miley Cyrus, Linda Sarsar, Malala Yousefrai and Carly Fiorino all consider themselves to be ‘feminists’. If any word could describe New Wave Feminism, it’s ‘inclusiveness.’

The movement is defined by intersectionality; the idea that an individual identity is affected by overlapping social categories of race, class and gender.

That inclusiveness means that there are many definitions of feminism today. Some are apolitical, economic, and others are cringe-worthy. For instance, some feminists will disapprove of me, a man, writing on the topic of feminism at all. Others will denounce the use of the word altogether, finding it too radical. Still others may say that empowering black women, or stopping the sexual assault epidemic on college campuses once and for all, or fighting for trans rights, is priority number one.

For me, feminism is the resolve which pushed my grandmother Marilyn on those hot Carolina days, in a society that kicked her not only because she was black but also because she was a woman. Delores didn’t protest sexist laws or study feminist literature. Neither of them may ever see a day when the genders of congresspeople reflect our society, or when our language no longer includes phases that enforce gendered norms. But their lives are crucial to my idea of New Wave feminism.

I see my own place in feminism as honoring the sacrifices my grandmothers and other ancestors made. I must continually unpack my privilege provided by my class, gender, ability, and race. That means learning how society treats me and observing how I treat others as a light-skin-toned, African-American, Straight, able-bodied, man. That means actively seeking chances to learn from women who are explaining their experiences. It also means I must be uniquely focused in any situations with law enforcement, as there is always the chance that an officer might think the same of me as one of my classmates did in middle school — they might believe that I will “never be equal to and never as good as” my white classmates. All of this reflection, I trust, strengthens me as a feminist.

I hope this idea of a reflective, inclusive feminism continues to grow. Delores and Marilyn and pioneering women like them, deserve for their own stories to be honored at last, in Rep Maloney’s Museum. Check out the legislation here on BillCam.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.