“Why the Dark Ages Were Never Dark”

Originally posted on the author’s Substack

An age of enchantment…

Between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and the Renaissance nearly a thousand years later, there lies an interesting in-between period — a “middle age.”

The early medieval period, known to many scholars as the “Dark Ages,” is often maligned as a cultural desert of barbarism, ignorance, and violence. Its cultural achievements get less attention than the splendor of classical civilization on one side, and the beginnings of modernity on the other.

The truth is that the Middle Ages were alive with their own vivid culture, history, and artistry, but modern perceptions are often blind to it.

Here are 4 facets of culture that reveal the light of the so-called age of darkness…

1. An Enchanted Worldview

Have you ever wondered why so many fantasy novels are set against a backdrop of a medieval-inspired era?

The epic, enchanted world of fantasy is virtually inseparable from the Middle Ages. The time period was charged with a pervasive wonder — medieval Europe had what’s called an “enchanted worldview.”

Essentially, it saw the natural world as intermingling with supernatural forces. Interacting with those forces became part of a larger story of the battle between good and evil. It imbued normal people’s everyday actions with a sense of meaning, adventure, and heroism.

These elements, all features of a medieval worldview, are inseparable from the fantasy genre. It’s no wonder the Middle Ages gave rise to works like Beowulf, The Song of Roland, and the Arthurian legends that still linger in our cultural consciousness today.

A world full of elves, prophecies, wizards, dragons, castles, and knights might sound like a Tolkien fan’s dream, but of course there’s danger in romanticizing the Middle Ages. There’s no denying that life during these centuries was rugged and brutal.

But at the same time, medieval life was more than a struggle for survival: it was a world charged with meaning and mystery. Framed by the Christian story, its worldview was saturated in the drama of good and evil, with every person understanding their life as a piece of this great narrative.

It’s no wonder epic stories like Tolkien’s find their expression in the medieval worldview — and no wonder that, in our disenchanted world, readers find themselves drawn again and again to the light emanating from this era.

2. The Nine Worthies

The Nine Worthies were a set of heroic figures from history and legend, celebrated throughout the Middle Ages as paragons of virtue. Divided into three groups of three — pagan, Jewish, and Christian — they included Hector of Troy, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Joshua, David, Judas Maccabeus, King Arthur, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon.

What made the Nine Worthies so enduring wasn’t their accomplishments, but how they inspired the medieval worldview. They weren’t seen as distant, untouchable icons — rather, they were considered models for the everyday person, heroes whose virtues could be emulated in daily life. In a world where life was often precarious and uncertain, these figures offered a way to aspire to something higher.

Each of the Nine Worthies embodied different virtues. Hector exemplified loyalty and honor. King Arthur stood for justice and chivalry. David embodied faith and courage. Together, they represented a universal framework of values that transcended time and, when properly lived out, served to build the foundation of peaceful and prosperous societies.

The enchanted worldview of the Middle Ages is reflected in the Nine Worthies. Their lives were seen as part of a larger cosmic story, where every act of heroism, loyalty, and faith echoed eternal truths. By aspiring to their virtues, everyday people were able to participate in the same cosmic battle of good versus evil.

3. Iconography

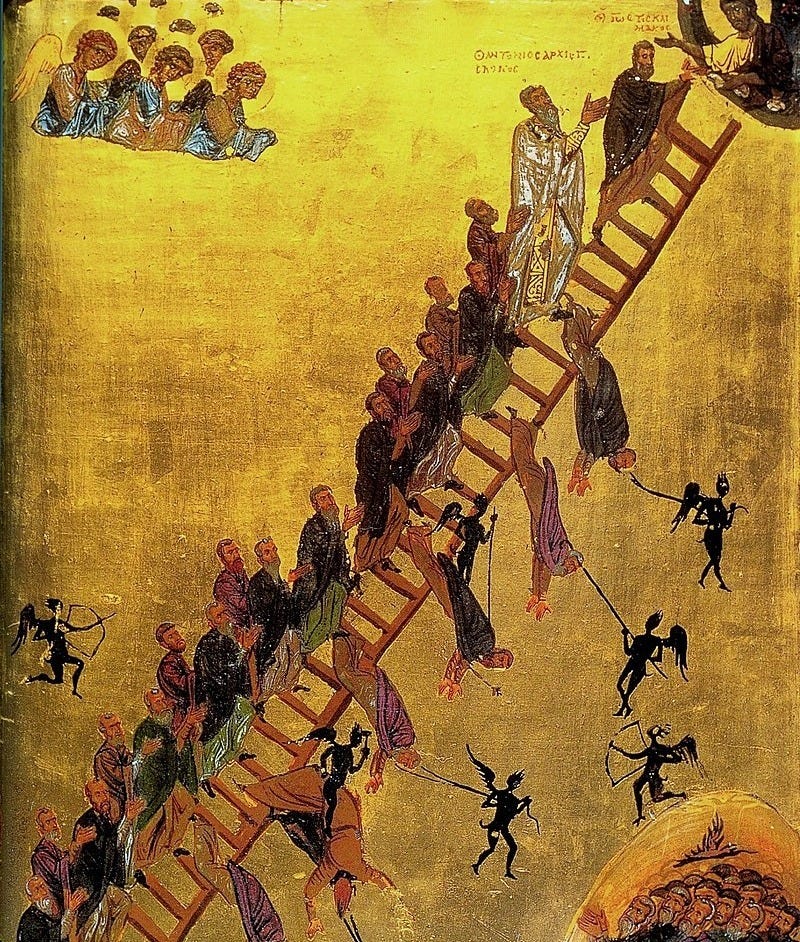

Unlike the art of the Renaissance and later, iconography isn’t trying to show you an artist’s subjective vision. Instead, it’s showing you reality through the eyes of the faith — like “windows to Heaven.”

And contrary to later art forms, iconography isn’t concerned with realistic details. To a modern, post-Renaissance viewer, that can be confusing…

Icons typically depict a person or event from the Bible or the history of the Church. The visual language is complex:

- “Flat” landscapes: no vanishing point or perspective, keeping the focus on the figures, not the background

- Multiple parts of a story in the same frame (even if they happened sequentially) — to demonstrate they are part of the same spiritual event

- Perfectly proportioned saints, regardless of their real appearance — to demonstrate that holy people are in harmony with themselves

It’s the very strangeness of the iconographic language that allows it to take on a sacred perspective. Its surreal depiction keeps it untethered to a particular time or place — so that its story remains accessible in all times and places.

Iconography was common to most religions of ancient times, but its Christian form gained ground when, in 330 AD, the Roman emperor Constantine moved the empire’s capital city from Rome to Byzantium. He sought to shed the failing cultural and political milieu of the old capital and establish a “new Rome”, to integrate the power of the ancient empire with the glory of the new Christian religion.

This fusion of old and new is what made iconography so powerful. Christian iconography took cues from Greek and Roman art, while absorbing the symbolic riches of its Judaic roots. It used these ancient modes to depict new saints and doctrines, creating a system of communication that made the faith accessible to everyone, regardless of literacy.

Because iconography looks strange — perhaps even stuffy and stilted — to the modern eye, it’s easy to mistake it as a mere precursor to later forms of art. But it has its own discipline and power. Medieval people saw icons as windows to the divine, and filled their homes and churches with icons intended to let in the divine light.

However, their visual impact is hard to gauge when seeing them on a page or in a museum. If you want to come face-to-face with this light from the dark ages, it’s best to find them in their natural habitat: under candlelight in centuries-old churches.

4. Gregorian Chant

Before the brilliance of Beethoven or the magic of Mozart, another kind of music spread across Europe. This music — as haunting as it is ancient — used no instruments and wasn’t performed in concert halls. Nonetheless, it quickly became the musical lifeblood of the Middle Ages.

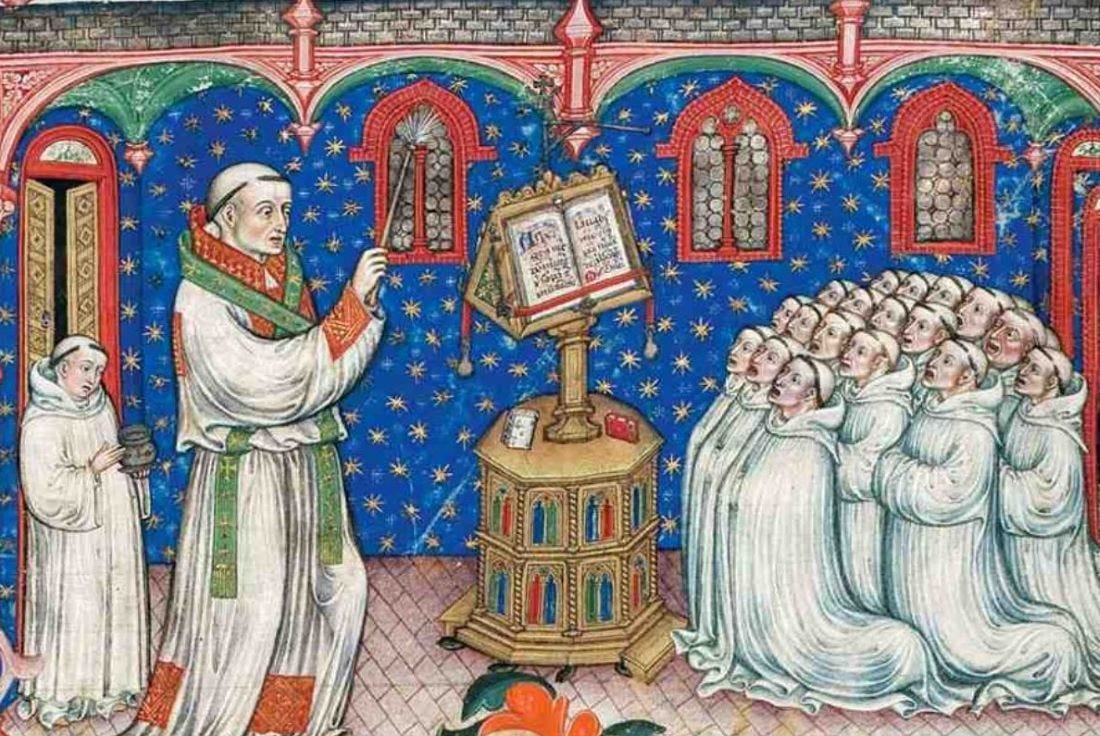

Gregorian chant grew out of the Judaic practice of chanting Psalms. In monasteries, where monks were required to recite Psalms seven times a day, chant was necessary: it allowed them to standardize their liturgies so that they could sing together.

Still, the early centuries of the church saw a proliferating patchwork of singing styles: communities developed their own variations, and certain figures like St. Ambrose left behind their own personal influence.

It wasn’t until Pope St. Gregory ascended the papal throne that chant gained the recognizable form we know today. Under Gregory, Christian chant became relatively standardized in a form that still bears his name today.

Chant was such a cornerstone of medieval life that it (quite literally) shaped cathedrals — architects designed churches for auditory aesthetics, just as much as visual ones. The acoustics amplified singers’ voices so that a single chanter could be heard throughout the entire building, and seconds-long reverbs came from a single note.

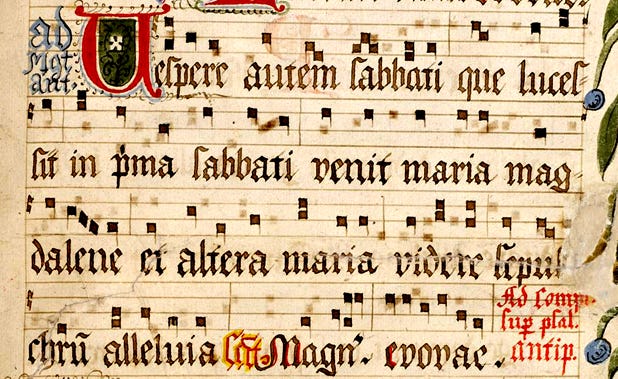

Without Gregorian chant, the great classical music of later centuries wouldn’t exist. It pioneered musical notation (using four lines and large blocks to mark notes), and this method of sketching down and reading music would later develop into the modern 5-line staff that’s still used today.

But Gregorian chant is more than a precursor to classical music. It’s a stunning art form of its own. When you listen to it, you won’t hear the dramatic highs and lows of later classical music, and it doesn’t explore an individual artist’s vision or emotion.

Instead, it’s like the voice of the ancient past — solemn and remote, yet profoundly peaceful. You can feel the weight of millennia of history, and it still haunts us.

If you’re skeptical, try listening to a recording, or better, find an in-person performance. You’ll find that it shares the voice of the faith from centuries past, and the beauty that sustained generations through unimaginably precarious times.

Drama in the Darkness

Toward the end of the medieval period, Renaissance art exploded onto the cultural landscape and drastically altered our attitudes and assumptions about what art is. That makes it relatively easy for a modern person to relate to the cultural output of the 15th, 16th, and subsequent centuries.

But peering further back in cultural history reveals a stranger and more challenging time. The creations of earlier centuries are less intuitive to us. But that doesn’t mean the Medieval era was the cultural nadir that the term “Dark Ages” implies.

The medieval era engaged with a mythologically rich universe, not focusing on individual artists but on the adventure of living — its art reflects the glory of that enchanted worldview…

_________

Follow DailyClout on Rumble! https://rumble.com/user/DailyClout

Please Support Our Sponsors

Birch Gold Group: “A Gold IRA from Birch Gold Group is the ultimate inflation hedge for your savings in uncertain times. Visit www.birchgold.com/dailyclout to see how to protect your IRA or 401(k).”

NativePath: “This Unique Protein Is Causing ‘A Paradigm Shift In The Fields Of Dermatology and Cosmetics.’…Visit https://getnativepath.com/DailyClout to learn more.”

The Wellness Company: https://dailyclouthealth.com

Use code DAILYCLOUT for 10% off!

Patriot Mobile: “Visit https://patriotmobile.com/dailyclout for a FREE month of service when you switch!”

Order ‘The Pfizer Papers’ and Support Our Historic Work: https://www.skyhorsepublishing.com/9781648210372/the-pfizer-papers/

Discover LegiSector! Stay up-to-date on issues you care about with LegiSector’s state-of-the-art summarizing capabilities and customizable portals. No researchers needed, no lobbyists, no spin. Legislation at your fingertips! Learn more at https://www.legisector.com/

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.