“‘Shark Tank,’ Abraham Lincoln and the Super Soaker: An Unconventional History of U.S. Patents”

Originally posted on Baltimore Sun

What do “Shark Tank,” Abraham Lincoln, and the Super Soaker have in common? Each has played a part in America’s longstanding and unique history of honoring the inventors who make life better for everyone.

Most people who watch “Shark Tank” don’t realize the 10-minute pitches they see are an edited version of a full pitch, which can last two hours. The Sharks almost always ask, “Do you have a patent?” The answer can easily be the make-or-break moment where the deal comes to life or falls through.

The Sharks are savvy enough to realize the irreplaceable role that patents play in American business, a concept our Founding Fathers also understood. Among the 4,543 words of our U.S. Constitution is the Patent Clause — Clause 8 of Article I, Section 8. It reads: “The Congress shall have Power… To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

Technically, patents date back to medieval times. However, the earliest patents were either difficult to obtain, extremely difficult to enforce, or both. Patents were granted only by the sovereign, which meant that if an Englishman wanted one, he had to gain an audience with the King of England. That put patent protection entirely out of reach for the “garage inventor.”

Even in Colonial America, the patent system was ineffective. Samuel Winslow holds the distinction of having received the first “patent” in America for his improved process for making salt. However, the patent was issued by the State of Massachusetts in 1641, making it impossible to prevent counterfeiters from stealing his process in other colonies.

The Patent Clause ushered in a new epoch in the history of governance. President George Washington was such a strong proponent of a federal patent system that he made special mention of this in his first speech to a joint session of Congress, urging members to create a workable system for granting patents and copyrights. Just a few months later, Congress passed the Patent Act of 1790, with the Copyright Act of 1790 hot on its heels. Two months later, U.S. Patent No. X000001 was issued to Samuel Hopkins for an improvement “in the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process.” This first patent was signed by Washington himself.

Not all of the Founding Fathers were so enthusiastic about an American patent system. Thomas

Jefferson had concerns about how patents would create monopolies in the free market. Eventually, Jefferson changed his position, even going so far as to suggest that the Bill of Rights include an 11th amendment granting inventors the right to their inventions.

By 1790, the once-skeptical Jefferson was made the de facto head of the American patent system as secretary of state. This time-consuming task was eventually moved from the secretary of state’s plate, but Jefferson remained a strong advocate for the American patent system. History would quickly show why.

America’s pioneering patent system explains the prosperity we have enjoyed for generations. With the right to secure the profitability of inventions made accessible, America had all the fuel needed for the engine of economic and industrial success.

Inventing a new world

Baltimore was an early hub of this innovative spirit. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O of Monopoly game fame) was the first common carrier railroad in America. It was founded in 1828 with the slogan “Connecting 13 great states with the Nation.”

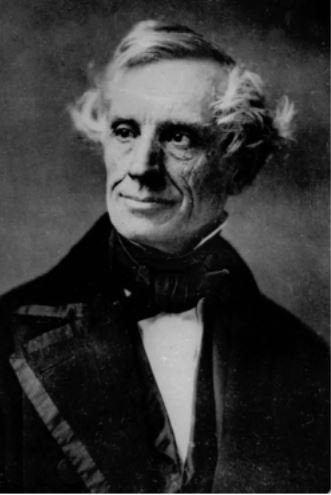

Another milestone in the history of U.S. patents came from Baltimorean Samuel F.B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph machine. The first telegram was sent from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore on lines laid along the B&O Railroad. The immortal words, “What hath God wrought?” were the first of many sent through Baltimore on telegraph lines.

American patents haven’t always been about business — some have just been about fun. When carbonated sodas came on the scene, producers were confounded by the leakage that would inevitably result when a cork was placed in the neck of the bottles. Only when Baltimorean William Painter came along and created the Crown cork bottle cap and opener that carbonated beverage distributors had a reliable way to seal their precious cargo.

Painters’ story is just one of many that epitomize the connection between America’s patent system and the American dream. Painter was a mechanical engineer from Triadelphia, Maryland, who moved to Baltimore to seek his fortune. He invented several useful items, including a paper folding machine, a safety ejection seat for passenger trains, and a machine for detecting counterfeit currency. None of these took off like Painter had hoped, but he was determined to change the world nonetheless. His invention of the bottle cap did exactly that, launching the small-town inventor to the head of a Fortune 500 company that still exists today.

Another great inventor in American history is boxing legend Jack Johnson. Not only was he the first African American to secure the title of heavyweight boxing champion in the early 1900s, but he was also a prolific inventor. Johnson was sent to prison on questionable charges for having a relationship with a white woman, but even from prison he successfully filed for two patents. (He was pardoned posthumously by President Donald Trump.) A determined inventor can even work from a prison cell.

The stereotype of the “garage inventor” is far from a myth. Many people passionate about changing the world have taken up inventing as a side hobby. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin are two that immediately come to mind. Yet, few realize that Abraham Lincoln holds the distinction of being the only U.S. president to have a patent in his name. As a young lawyer in Springfield, Illinois, Lincoln devised a system by which riverboats could be lifted out of sandbars, saving crews the unpleasant task of having to unload their ships to lighten the load. The model of Lincoln’s invention submitted with the patent application is considered a valuable artifact in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Another such inventor is Lonnie Johnson, an African American former nuclear engineer who turned his work for the U.S. Air Force into one of modern history’s most prolific (and fun) weapons: the Super Soaker water gun. While working on a heat pump connected to a sink in his home, Johnson sprayed some water across the bathroom. It occurred to him that a pressurized water gun would make a great toy, and the rest is history. According to the current manufacturer, sales of Johnson’s Super Soaker are approaching $1 billion.

To any prospective new inventors, the moral of Johnson’s success story is simple: If you have an idea that improves the lives of enough people and you have the determination to see that idea through to fruition, our U.S. patent system will protect your right to be justly compensated by the free market.

Without protection, patents are worthless

Without the patent system, the world might not have been able to experience the ease of travel on America’s railways, faster communication with the telegraph machine, the refreshing taste of carbonated beverages, or the fun of backyard Super Soaker warfare. The beauty of the system is that those inventions that are most beneficial to society are also the most capable of turning a handsome profit.

However, this brilliant process that Americans pioneered is not without its threats. Enforcement of the patents is vital. If thieves aren’t prosecuted for stealing ideas protected by patents, then the patents are worthless. While U.S. courts are good at protecting patents, increased globalization has made it more important than ever for American patents to be honored throughout the world.

However, this brilliant process that Americans pioneered is not without its threats. Enforcement of the patents is vital. If thieves aren’t prosecuted for stealing ideas protected by patents, then the patents are worthless. While U.S. courts are good at protecting patents, increased globalization has made it more important than ever for American patents to be honored throughout the world.

Yet, certain countries not only permit but encourage the theft of American patents. China is one of the chief offenders. A survey from CNBC indicated that around 20% of U.S. corporations say that China has stolen their intellectual property within the last year. This costs between $225 billion to $600 billion per year in revenue for American businesses, according to a congressional study. These thefts come from traditional corporate espionage or dramatic cyber attacks like one in 2022 where the Chinese state-sponsored hacking group APT 41 stole trillions of dollars of intellectual property ranging from manufacturing blueprints to plans for missiles and fighter jets.

Another looming threat is artificial intelligence. The emergence of dramatic AI tools may seem like magic to the average user, however, generative AI models are trained from data sets containing billions of pieces of information from the internet. Depending on a particular AI model’s data set, a significant amount of copyrighted or patented material feeds it.

This leaves courts to ponder the key question: Is the data that feeds an AI model covered by the fair use doctrine? If so, AI companies can take the ideas of others indiscriminately and use them to shape responses from generative AI models. If not, AI companies would have to pay for protected work, which could substantially limit their overall capabilities.

The other side of the coin is the products that emerge from a generative AI model. When a user requests a picture of a remote beach scene with whales breaching on the horizon, who is the rightful owner of that computer-generated image? Does it belong to the creator of the AI model, or the user who created the parameters within the prompt itself? As AI becomes able to create patentable innovations in technology, medicine, or other fields, who will rightfully hold those patents?

Artificial intelligence is creating a new wing of intellectual property law that is just now being tested in courts. These cases will map out the future of artificial intelligence and intellectual property as we know it.

Despite these challenges, the U.S. patent system remains an indelible part of the American dream, where notoriety and financial gain is possible for any inventor, regardless of their background or status.

Now more than ever, America is a land of creators. We have a boundless thirst to leave our marks on the world by building something that lasts. For those who invent, the usefulness of their creations can extend far beyond their lifetime, shaping a world that is better for everyone.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.