Reading, Understanding, and Interpreting Medical and Scientific Literature – Assisting the Neophyte.

Recently Modern Discontent published a paper on Substack that proves to be a worthwhile guide for those new to reading medical and scientific literature. “Modern” represents himself/herself as a:

“Disaffected Scientist, Disaffected Liberal. Trying to make sense of things and ranting about science, culture, and the world beyond.”

https://moderndiscontent.substack.com/p/how-i-tackle-reading-papers

This article does an excellent job of explicating the common features of technical medical and scientific papers and will help the novice understand the structure and interconnectivity of the various elements of technical writing.

The flow of such work begins with laying a foundation with mention of relevant literature. Next comes defining the matter to be presented including hypothesis testing for the more rigorous work. Methodology, data presentation, interpretation of the data and conclusions then follow.

The goal is to present an idea and support it with data, not to entertain or engage the reader. Science is a tool to be used for discovery or confirmation and not something to be “followed” like a baseball game.

Contrast this type of writing with a lay piece that often hints at the conclusions early as a “grabber” and has an entirely different purpose, interest and readability as well as actual structural differences.

The subject matter of this Substack, and mRNA gene therapies more broadly, is a complex and sophisticated blend of experimental design, statistical analysis, data presentation, immunology, virology, organic and biochemistry, physiology, epidemiology and internal medicine to name a few disciplines.

One can approach this literature from a broadly based background in these various disciplines, a very narrow and focused background in one specific aspect, or from that of an interested “outsider.” At times, the terminology and symbols used can be daunting, even to experts in different but related disciplines. Do not give up!

Medical/Scientific Terminology

It helps to take notes of important points and unfamiliar terms, as well as to look up the latter and record the definitions. Eventually, they will begin repeating, and you can fill in areas that were not clear at first. Medical literature on the subject of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 is open source, and you can download a PDF copy to mark up of almost everything published. Medical literature otherwise is often behind a paywall.

Consider the following example. The term CD4+ lymphocyte seems pretty opaque, so the reader will need to look it up. An internet search turns up the following first hit:

CD4 Lymphocyte Count

What is a CD4 count?

“A CD4 count is a blood test that measures the number of CD4 cells in a sample of your blood. CD4 cells are a type of white blood cell. They’re also called CD4 T lymphocytes or “helper T cells.” That’s because they help fight infection by triggering your immune system to destroy viruses, bacteria, and other germs that may make you sick.“

https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/cd4-lymphocyte-count/

A further search reveals that white cells come in five versions: neutrophils, lymphocytes, basophils, monocytes and eosinophils; and now the reader knows about one of them.

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/327446#types-and-function

You get the idea and can now go deep into one of the cell lines or take the knowledge you have gained and go back to the article. You can still go deep later but in small quantities. With repetition, your knowledge will grow commensurate with your effort.

Peer Review meets Forensic Analysis

The postings I made concerning the Phase 1-3 clinical trials on my Substack were meant to display the type of notes I would take in working up a peer review – although the notes portion would not go to the in-house editorial staff, only the comments and questions.

Since my reviews were meant to be references for later work, what I published was not a finished review but a free-form version that could be made into the document to be submitted to the Editorial Board, if that was the task. But, in this case, it was not.

In the case of the CDC and FDA report based on Shimabukuro, et al. [https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa2104983], another skill set had to be drawn upon. A forensic analysis was necessary for a variety of reasons, which you will get a flavor of by reading my last two reports. [https://dailyclout.io/data-do-not-support-safety-of-mrna-covid-vaccination-for-pregnant-women/ and https://dailyclout.io/report-40-2021-cdc-and-fda-misinformation-retroactive-editing-erroneous-spontaneous-abortion-rate-calculation-obfuscation-in-the-new-england-journal-of-medicine/]

The 60-plus page peer review comprising these two articles is distinctly unusual and was warranted by the distinctly unusual nature of the CDC and FDA reporting in Shimabukuro, et al.

Additional Comments to Supplement the Work of “Modern Discontent”

Materials/Methods (m/m) and Results (r) are where you will find the meat of the paper. Abstracts and conclusions should accurately and precisely line up with m/m and r.

The discussion needs to address systemic and random bias(es) and how they impact the results. When doing peer review, I work over any numerical data to compare it with the authors’ presentation of results. It was striking in the Shimabukuro, et al. paper how skewed their data was. This should have been covered in the discussion. It was not.

Just below the title, the reader will find the author list. Institutional affiliations should be checked to see who and what institutions collaborate. Also, look at the chronology to see when the work was received, revised, published, etc. Editors are under tight deadlines. When I first began peer review, I had a month or more to turn around a paper. The last paper I reviewed had a 14-day deadline.

A review may take a few hours. Or, like my review of the Shimabukuro, et al. paper, it may take 50 to 75 hours or more. That review was so lengthy because I combined peer review with a forensic analysis so it could be used as a court document.

Peer review, by the way, is seldom compensated and is rarely acknowledged, but it offers the reviewer an opportunity to see what is coming down the information highway before widespread distribution. But, even rejected articles never published can be edifying for the reviewer.

If I think additional expertise is required, I obtain it and then acknowledge the consultant in writing. If I do not know a qualified consultant, say a statistician, I tell the editor; and he or she finds a statistician.

Three corresponding reviewers then send their reports by email after grading the paper and adding commentary and questions for the authors, and then the in-house panel makes a final decision. The authors are notified. Rejection is easy, but revision recommendations can be lengthy.

Footnotes in medical papers sometimes are very important. For example, in the now familiar “Confidential Pfizer Document 5.3.6” [https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/reissue_5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf] summarizing Adverse Events (AEs), there is a small-print notation about a 28-day-old baby who received a BNT162b2 injection, and no additional information is given.

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/reissue_5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf, p. 25]

What?!?! And what happened to the baby? What dose was given? Unfortunately, there was no follow up for this unfortunate neonate.

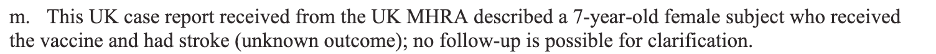

There are more stories like this last one. A seven-year-old was listed in small print as having had a stroke:

[https://www.phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/reissue_5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf, p. 25]

What is going on? This product was NOT approved for children!

Again, no follow-up or discussion. How did this even happen? We better know what since the drug was not approved, Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) or otherwise, for children. This should have been a red flag event!

Finally, at the bottom of the last page of a medical or scientific paper, the notes disclose potential conflicts of interest and funding sources.

Now, go back and look at the “Abstract” and “Conclusions” sections to assess whether the Materials and Method and Results support the conclusions and are accurately presented in the “Abstract.” Conclusions should be precise and accurate representations of the data. Biases should be assessed and taken into consideration.

That is all there is to it.

Now, try to get through one article per week, and you will find your expertise in reading, understanding and interpreting medical and scientific literature grows.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.

I am paid 114 dollars per hour to perform certain internet services online. I had no idea it was feasible, but my closest friend joined and earned $27000 in just five weeks by doing sac-20 this simple task. Visit for greater information about visiting this page. Anyone may obtain this right away and begin making money online.

by following the directions on this website………………. https://dollarcareers20.netlify.app/