Elon Musk’s Brain-Tech Company Withholds Records After Research Leaves 15 Monkeys Dead

Elon Musk’s brain-tech company withholds records

after research leaves 15 monkeys dead

As Musk rides the free speech wave, doctors group sues for access to video footage of experiments it claims are public records.

Elon Musk may have achieved iconoclast status in the culture war with his $44 billion takeover of Twitter. And while the internet has been apoplectically prophesying about the fallout expected from his leadership of the platform, another company in his ever-expanding portfolio has largely shielded itself from a little-reported controversy involving 15 dead monkeys in a California primate research lab.

On February 11, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service confirmed it would look into experiments conducted for Musk’s brain-tech company Neuralink. This came one day after a doctors group, Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), filed a complaint alleging that the experiments violated the federal Animal Welfare Act.

The experiments were done by the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at University of California, Davis, which Neuralink contracted in 2017, towards the development of a brain-machine interface (BMI) that will ostensibly help people with paralysis regain independence. According to a statement from PCRM, UC Davis received more than $1.4 million from Neuralink to conduct the research. Neuralink stated that its reason for commissioning UC Davis was to conduct foundational research while it constructed its own in-house animal program. The course of research included at least 23 rhesus macaques (the most-used primate in biomedical research), 15 of whom died.

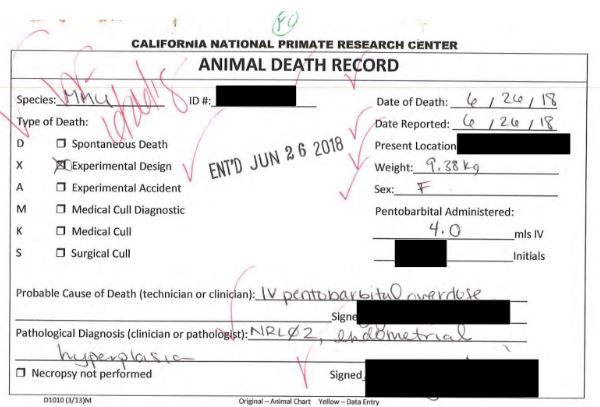

The complaint followed a series of legal actions taken by PCRM, beginning in 2021, to compel UC Davis to release records related to the research, resulting in the disclosure of nearly 600 pages of documents, including surgical logs and necropsy reports. (Photos and videos of the experiments were not included. More on this below.) The documents illustrated a process of drilling into and removing portions of monkeys’ skulls, and implanting electrodes into their brains.

In the complaint are allegations that eight Animal Welfare Act regulations were violated, including the requirement that procedures “must avoid or minimize discomfort, distress, and pain to the animals”, and “discomfort and pain to animals will be limited to that which is unavoidable for the conduct of scientifically valuable research.” The complaint leans solely on the released documents to substantiate the interpretation that violations occurred. The documents show, for example, that one monkey was euthanized after the area around the implant in his or her head became infected and required frequent cleaning and flushing with “copious amounts of antibiotics”. In another example, a 7-year-old monkey experienced seizures, an eye infection and reduced appetite following an implantation.

Also disputed is the use of BioGlue, a surgical adhesive, which PCRM states was not approved for use in this research and is known to be toxic to nerve tissue (confirmed by an FDA safety document that states “avoid exposing nerves to BioGlue.” The document also warns that “BioGlue contains a material of animal origin which may be capable of transmitting infectious agents.”) Records show the substance “came into contact with the surface of at least two monkeys’ brains, causing damage and hemorrhaging.” In one account, a surgeon “had concerns about the void in between the two implants and applied BioGlue to fill the dead space.” A necropsy report revealed the presence of BioGlue on the monkey’s brain. Neuralink acknowledged the euthanasia of one monkey due to complications related to the “use of the FDA-approved product (BioGlue),” implying that the use of the substance was above board.

In Neuralink’s only public statement addressing the controversy, it rejects outright the claim that any regulations were violated: “the facilities and care at UC Davis did and continue to meet federally mandated standards.” However, Neuralink seems to distance itself from UC Davis, instead emphasizing the ambitious and progressive animal care standards of its in-house facility, to which it migrated its research operations as of 2020. It says: “We absolutely wanted to improve upon these standards as we transitioned animals to our in-house facilities.” This is hardly an enthused endorsement of UC Davis. Neuralink also appears to lack remorse for any suffering the monkeys may have endured, noting that many of the procedures were “terminal” (meaning the animal’s death is implicit in the procedure). Neuralink says: “These animals were assigned to our project on the day of the surgery for our terminal procedure because they had a wide range of pre-existing conditions unrelated to our research.” In other words, the animals were going to die anyway. Contrast this with Neuralink’s animal welfare ethos: “It is our responsibility as caretakers to ensure that their experience is as peaceful and frankly, as joyful as possible.”

It is a noble sentiment, but Neuralink’s judgment and seriousness about animal welfare are questionable, not only given the lack of remorse shown, but also when UC Davis’ recent record is considered. In 2019, the Daily Democrat reported the deaths of seven baby macaques at UC Davis caused by the transfer of a chemical dye from mothers to babies (the incident was originally reported in The Guardian). Additionally, from 2013 to 2019, UC Davis received 24 citations for violations of the federal Animal Welfare Act. For example, as PCRM notes in a legal filing, “in 2013, a macaque became trapped in the ‘squeeze mechanism’ of his cage and died ‘as a result of trauma to the head and neck.’” Even if these citations represent a small percentage of UC Davis’ total animal program, suffering and death aren’t to be taken frivolously as statistics void of moral content. And if Neuralink is to position itself as a progressive example in the animal welfare space, why would it commission to kick off its research an institution with an imperfect record?

This complaint, however, is not expected to add any more blemishes to UC Davis’ record. Ryan Merkley, Director of Research Advocacy at PCRM, commented that while the USDA is looking into the complaint, it is unlikely to find any violations as it is historically “industry-friendly.” As strength of evidence goes, Merkley is particularly confident in this complaint, based on the documents he and his team spent more than a week poring over.

And while the documents are revealing, there are huge gaps and insufficiencies, including copious redactions, and the ongoing absence of photo and video records, which would give deeper insight into the compliance (or lack of) with federal animal welfare standards and protocols. On this front, PCRM filed a second lawsuit in February asking the State of California to compel UC Davis to release all photos of the research conducted for Neuralink, under the California Public Records Act (CPRA). The suit claims that UC Davis violated the law when it cited a catch-all exemption to disclosing what would otherwise be public records. The exemption argues that public interest in withholding the photos clearly outweighs the interest in their disclosure.

The suit foregrounds a tension between public and private entities where records are concerned. If a private company engages a public institution to perform services, do records related to the work belong to the private entity, or do they fall under the relevant public records legislation? CNPRC also receives public funding well in excess of what it received from Neuralink (in 2020, more than $11 million from the National Institutes of Health). What’s public? What’s private?

The situation surrounding the missing video records leaves even fewer legal levers available to advocacy groups and the public; according to UC Davis, videos of the research were captured on Neuralink equipment, which was removed when the contract ended. Merkley said PCRM’s lawyers sent a letter to Neuralink warning the company to retain the video records (as in, not to destroy them) in case those records become relevant in a legal ruling. PCRM would not share a copy of the letter.

In the meantime, Neuralink has published a series of PR-friendly (if macabre) videos of post-implant animals performing tasks, looking relatively content. In one video, published on YouTube in August 2020, an animal care team dotes over a trio of pigs who live in a white, clinical room with hay, a cold simulation of their outside habitat. Such videos are meant to assure the public that animals are happy to be on the Neuralink team, contributing to science and technology that will benefit human health. Noteably absent from Neuralink’s public materials are videos and images of the surgeries conducted on the monkeys at UC Davis. As Neuralink attempts to sweep its first chapter under the rug and look forward, the public records lawsuit may be the only chance the public has of ever seeing a full picture of what happened at UC Davis.

“[UCD] cannot justify blanket withholding of the photos and video footage all the while assisting a private company as it opportunistically publicizes portions of the very same public records to raise its commercial worth.”

-PCRM petition to the State of California

Where does Musk fit into all of this? Well, his brand is thwarting the status quo, in a way. He’s the fusion of the global elite and a teen agitator who doesn’t like convention. It shows in his other companies.

For Twitter’s next chapter, he has espoused a transparency ethic that could be a welcome breath of fresh air for those who felt Twitter was losing oxygen from partisan moderation. Unfortunately, this ethic has not carried over to Neuralink. Granted, animal research is notoriously clandestine, so this is not a Neuralink anomaly. But Musk is the great disruptor, and Neuralink states openly that it sees an animal-free R&D paradigm in the future. If the company is truly committed to this, Musk still has a chance to return to first principles and disrupt this space like he has with others. He can use his abundant resources and sixth sense for innovation and put a moratorium on any further animal research at Neuralink, full stop. He can prove there is a way out of the animal model that isn’t incremental. Sometimes it’s just a matter of tearing off the band-aid.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.