‘The Bergdahl Case is a Window Into Our National Fiction on War and Patriotism’

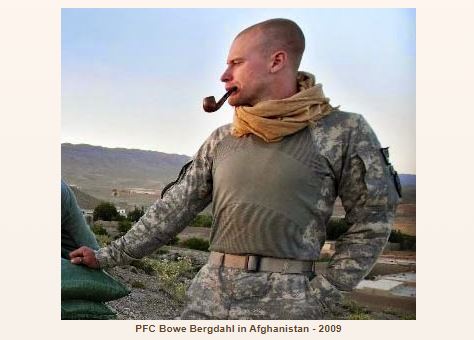

A striking 2009 photo of one of the nation’s most talked about people, Bowe Bergdahl, recently surfaced: the then 23-year-old, wearing his Army fatigues and a yellowish scarf around his neck, is standing at an Army outpost in Afghanistan. He is smoking a pipe. His right hand is on a sand bag, the left hand comfortably in his pocket. The young soldier’s entire pose, down to his right foot about to casually cross the left, bespeaks a man living in an alternate universe. That universe might well be one of classical Greek warrior statues, standing contrapposto, too confident in their martial mastery to be perturbed. Whatever Bowe Bergdahl was thinking when he struck that pose, it worked: the photo illumines a young man trying to square his conceptions of himself into a wartime reality that did not fit.

Public opinion polls on the Bergdahl-Taliban prisoner exchange don’t look good for the newly-freed 28-year-old: Most Republicans, according to one poll 71 percent, opposed President Obama’s prisoner exchange, while even among Democrats, according to the same poll, support for the deal stands at 55 percent. Simply put, there is no ticker tape kind of love affair between the American people and this soldier who once dreamed of military gallantry in faraway places, according to published accounts.

Perhaps one day the American public will find out if Bowe’s alleged inquiry to his platoon mates about hiking over the Afghanistan mountains to China is fact or fiction. Whatever the case, Bowe would not have been able to indulge his fantasies about war and his own being but for one overarching, yet entirely overlooked, fact: the civilian population of the United States began indulging in fantasies about war, and our own virtue, long before Bowe ever did.

Though there seems an increasing national awareness over the sheer immorality of sending a tiny portion of the U.S. population off to die in wars in the name of this country, while the rest of us are instructed to “go shopping” – as President Bush once told Americans – the American people retain something of a Bowe-like fantasy about our own personal attributes in a time of war. Like Bowe, many Americans have a compelling need to mark out their own virtue, specifically the virtue of love for country; putting “Support Our Troops!” bumper stickers on one’s car is a favorite.

Yet this gulf between documented displays of patriotic virtue and putting one’s body where one’s mouth is – or one’s bumper sticker – is arguably just one among many signs of our times. For instance, according to a recent poll by the Public Religion Research Institute, a certain portion of the American people are apt to inflate their weekly church attendance when asked. Social scientists refer to this as the “social desirability bias,” namely people knowing full well what is considered to be a socially desirable attribute, and doing what they have to do to project a distorted reality of who they are, in this case devout church-goers, and thereby win the respect of their peers. The poll begs the question: If some Americans are prone to inflating their religious observance for their own social advantage – thus distorting their relationship with God to do so – is it not reasonable to ponder if some Americans inflate their admiration for the troops – thus distorting their relationship with their country and fellow citizens – for the same darn reason?

Unless the U.S. military justice system files charges against Bowe Bergdahl and proves him guilty of a heinous wartime offense, nobody should be calling him a traitor. Based on now ample documentation in the public domain, Bowe is a young man whose heroic conception of himself and his own virtue was 180 degrees at odds with the reality of the war he found himself in. In a published e-mail to his parents before his disappearance, for example, in which he criticized the U.S. war in in Afghanistan, Bowe wrote, “I am sorry for everything…The horror that is america is disgusting.” Those are tough words indeed, and entirely indicative of an inner break of mind and spirit that led to what seems a reckless and dangerous decision to leave his post. As Congresswoman Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) stated this week in a House hearing with Defense Secretary Hagel about this prisoner exchange controversy, the military justice system will have to determine if Bowe’s actions met the precise legal definition of desertion.

But before casting stones at Bowe, the American people need to take a look in our national mirror: How are our own false conceptions about our devotion to country shaping our government’s response to the wider world?

Do you love America so much you are willing to die for it? For that matter, are you willing to die for NATO member states, like Poland, a country for which President Obama recently described U.S. military support as sacrosanct?

Let’s hope we grapple with the reality of who we are as human beings, and as Americans, before we repeat the same exploitative cycle of the last decade in yet some other part of the globe.

Until then, we are bound to heap the emotional burden of our national fiction – our embrace of national unreality – onto the shoulders of a tiny portion of young Americans, indulging as we do in that additional, and self-serving, fiction that it somehow doesn’t take two to Tango.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.