Is It Time To End The War on Drugs? Senator Cory Booker Thinks So.

If you want to see a Congressperson blush, ask him or her a question about marijuana. With four states (California, Massachusetts, Maine and Nevada) having legalized it last November — making that seven states and DC, where pot is now legal for recreational use — this is one topic that is becoming more and more unavoidable. Last year, one Senator decided to take marijuana legalization head on.

Last summer, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) introduced a bill to completely legalize marijuana at the Federal level. The Marijuana Justice Act would not only change the way the federal government looks at Marijuana from here on out, it would even offer Federal prisoners convicted of marijuana related offenses a chance to challenge their sentences.

The legislation doesn’t stop at marijuana use or the people convicted for marijuana-related crimes; much to the delight of supporters of ending marijuana incarceration and imprisonment, the legislation would keep states that disproportionately arrest minorities for marijuana offenses from building new jails with federal funds.

The collective altering to Federal law this bill proposed would have substantially changed many sectors of life in America, and Senator Booker’s introduction of this bill brought clouds of praise and protest. On twitter, he started a lively debate:

Some see the legislation as reasonable:

Others retorted with the dangerous effects of the drug, and still others replied:

https://twitter.com/satxangel/status/893457364355092484

It’s safe to say that the debate was lively, and reports of the harm marijuana can cause users have become more prevalent with the wave of legalization recently. But federally, the United States is not even at the level of weighing how dangerous Marijuana is. The Drug Enforcement Association or DEA’s stance on the drug maintains that it’s not even worth studying.

Currently, the DEA labels Marijuana as a schedule I drug. According to the DEA, Schedule I drugs possess “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Schedule I substances are “the most dangerous drugs of all the drug schedules with potentially severe psychological or physical dependence.” Marijuana shares the Schedule I designation with heroin, Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), Methaqualone, and Peyote. For reference, the schedule II drugs list, those “less dangerous” and with “less abuse potential than Schedule I drugs” include Cocaine, Methamphetamine and Adderall. When you compare this scheduling with public opinion, something doesn’t add up.

More than 60 percent of the country supports legalizing marijuana, up from a modest 31 percent in 2000. For people in the 18 to 34 range, support is even higher, with 77 percent in favor of recreational legalization. Nearly half of people in America have tried the drug.

Sen. Booker’s bill, in removing marijuana off the list of Schedule I drugs, takes a strong stance on the longstanding debate over the harm of legalizing marijuana. But his stance isn’t a very controversial one. If so many Americans support this kind of legalization, what’s the hold-up?

States’ Rights?

Marijuana was a fixture in young America. Early in the 1900’s, compounds from the marijuana plant could be found in apothecary shops, and the non-psychoactive part of the plant produced hemp. Hemp was used for rope, clothing, paper and many other products, but by 1934 recreational use was prohibited. To understand what happen in those 30 years, we have to look to where the prohibition began: El Paso, Texas.

It was the first city to ban “marihuana” as it was called by the growing Mexican immigrant population. The policy was in fact a reaction to the influx of Mexican immigrants who crossed the border as a Huerto presidency (a seventeen month term as president) ended in civil war and the Mexican Revolution reached its peak. Prohibition as reaction to an influx of immigration was not revolutionary, it was the rule of thumb in early America. The West Coast in the 1800’s saw many uses of opiates; housewives would often use the drugs to calm nerves. Then in the 1870’s an influx of Chinese immigrants who commonly smoked opium coincidentally were met with vicious rumors, headlines and eventually the Anti-Opium Act of 1909.

While similar stories underpin cocaine usage, prohibition always came with a non-white face attached. The New York Times was the most influential, headlining stories of dangerous, black cocaine users and laying the foundation for “Reefer Madness” with stories of mad mothers and children succumbing to the marijuana’s effects. But Federal legislation on marijuana didn’t come until the late 30’s. Wouldn’t you know, it was about the time Jazz came to prominence. The time of Jazz legends like Louie Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Cab Galloway — African Americans had brought a dance, style, smooth music and marijuana to the east coast. On went the propaganda and prohibition of the drug.

Before there was a DEA to stop the mostly African American counter culture’s “satanic music”, Harry Anslinger was the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. His quotes are infamous on the internet, all including the effects of marijuana on “degenerated races”. He testified vigorously and pushed a legislative agenda that sustained through the fifties with the Boggs Act and the Narcotics Control Act of 1956. Without any new information or uncovering of evidence the government restricted the drug with more and more voracity.

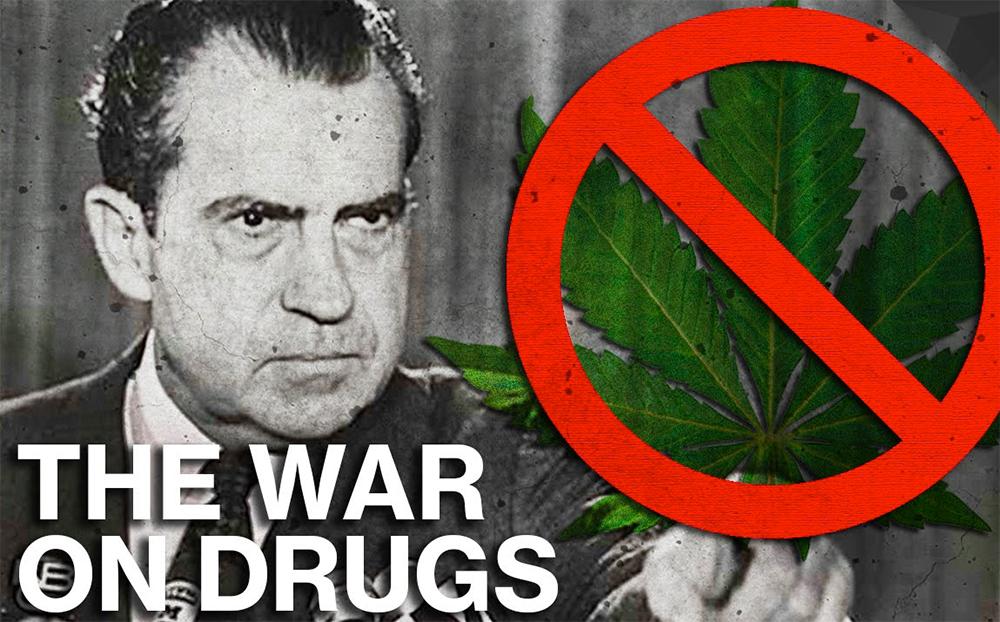

Part of the story often missed is the time between WWII and 1970. As PBS notes, numerous reports — including those commissioned by Johnson and Kennedy — found that the drug did not induce violence, and many other claims were debunked. Marijuana was also tied to a very popular counterculture and by 1970 many states had decriminalized it. It seemed science, logic and reason had won, until the Nixon Administration’s War on Drugs.

The War on Drugs began with a beacon of hope. The Shafer Commission, a bipartisan commission directed by Congress to study all aspects of drugs and the policies towards them. The commission yielded a report titled, “Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding” and on the status of drug policy they had this to say:

“The political pressures involved in this governmental effort have resulted in a concentration …on the most immediate aspects of drug use and a reaction along the paths of least political resistance…”.

The commission warned that there would be an ever increasing bureaucracy and public outcry that would endlessly leech public funds. Their greatest concern was “the creation, at the federal, state and community levels, of a vested interest in the perpetuation of the problem among those dispensing and receiving funds…”. Sound familiar?

“The prohibition of Marijuana began as a race problem, took off as a federal government initiative and is now being sustained in the name of federalism a.k.a. state’s rights.”

This study and thousands of pages of unbiased considerations that warn of the cost of heavy-handed, reactionary institutional drug policy, was in the hands of the Nixon White House.

And the “criminalization” began. Nixon, and then the Reagan, Bush, and Clinton Administrations, all ignored the information in the Shafer Commission report and waged a forty year War on Drugs. One trillion dollars later, the United States has more people in jail than any other country at an average of $30,000 an inmate.

Nothing in this history of prohibition hints that the prohibition of Marijuana has ever been about the freedom of states. Now, one could argue that this is a problem of states’ rights, but states aren’t the originators of this war on drugs; they didn’t establish asset forfeiture, imposed mandatory minimums, and three strikes laws. The prohibition of Marijuana began as a race problem, took off as a Federal government initiative and is now being sustained in the name of Federalism — a.k.a. states’ rights.

Not to mention, the legal contradiction our marijuana policy imposes. Recreational marijuana dealers in states where the drug is legal are subjected to extreme difficulties and even danger because of the federal laws. Banks won’t do business with them out of fear of retribution from the federal government. So, the banks don’t loan to weed entrepreneurs. And worse yet, because these businesspeople cannot use banks, they often end up traveling, and storing large amounts of cash– which makes them prime targets for criminals and law enforcement officials alike.

Simply put, the classic states’ rights argument can be used to flout change and oppose sensible policy, while ignoring egregious issues like racially disparate incarceration—a problem that’s more severe in some states than in others. The war on drugs cannot be solved piecemeal. Senator Booker’s legislation very substantially would have taken on multiple facets of this problem.

So, Does This Bill Have a Chance?

It’s important to note that this isn’t the first time Senator Booker proposed marijuana legislation; last time his bill garnered the support of two Republican Senators in Rand Paul (R-NV) and Mike Lee (R-TX), but still didn’t get out of committee.

What’s very different and perhaps very daring about the Justice Act, is that its passing would have the Federal government admit the discriminatory nature in which drug laws have been applied, but also aim to fix this by punishing the offending states. Detractors will rally that this bill denies state’s the freedom that the federalist system reserves for them, and that letting race run policy is unconstitutional. However, the reality of how marijuana prohibition began may help explain why Senator Booker (D-NJ) has taken this approach: at the federal level and based off of race.

In the end, we have to make a judgment on what’s more important: states’ rights or civil rights. Senator Booker has seemingly made a choice in favor of the later. Whether you agree with him or not, you should have your say.