What’s in the 371 photos Elon Musk and UC Davis don’t want you to see?

Public records lawsuit continues with document that says images of

monkey experiments are being withheld due to concerns of harassment and violence

While Elon Musk’s brain-tech company Neuralink may have left its days of conducting painful experiments on monkeys in taxpayer-funded facilities well behind it, its animal research program is now in-house. A lofty animal welfare statement sits at the top of the company’s blog, and a few rounds of PR showing how enriching Neuralink facilities are for pigs and monkeys seems to distract from the fact that these animals’ brains will soon have electrodes implanted in them.

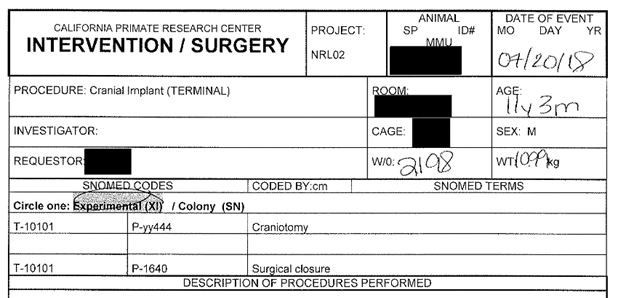

All of this has been paving the way to developing a brain-machine interface that Neuralink claims would help people suffering from paralysis regain independence. The research started in 2017 and was initially conducted at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at UC Davis and paid for by Neuralink.

Last year, a public records request– resulting in the disclosure of 600 pages of documents– was followed by a legal complaint alleging eight violations of the Animal Welfare Act. The documents detailed the procedure wherein portions of monkeys’ skulls were removed and electrodes inserted, as well as other varying circumstances that resulted in the deaths of 15 monkeys.

Photo and video records of the research were not disclosed and an ongoing public records lawsuit aims to compel their release to keep this research from being swept under the rug (and scrubbed from Neuralink’s history). In May of 2021, doctor’s group Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) sued UC Davis for refusing to release the photo and video records.

Last week, the firm representing UC Davis responded to a request for a Vaughn Index (a legal document describing withheld records and grounds for non-disclosure). I was provided a copy of this Index from PCRM. The Index outlines two sets of photos related to the Neuralink/CNPRC research.

The first set of 185 photos pertains to necropsy (autopsy) reports. They are used to assist pathologists in preparing said reports, and to “inform future research and clinical practices.” The Index also indicates that they are the photographic equivalent to note-taking and are not intended for public disclosure.

Among the reasons for non-disclosure of this set are concerns that without the contextual facts, the photos would be misinterpreted by the public. This implies that any objections to the content of the images would be misinformed and out of context. To the contrary, it’s possible (and legitimate) that the public would ingest the images with proper context and still have objections. PCRM research advocacy director Ryan Merkley puts it this way: “UC Davis thinks the public is too stupid to know what they’re looking at.”

Additionally, the Index argues that due to the graphic nature of the photos, their release could result in harassment of the researchers involved in the project– this risk alone would have a “chilling effect on future research.” The Index says:

“The interest in protecting the safety of public employees and ensuring research that benefits the public can proceed without risk of violence clearly outweighs the public’s interest in viewing said photographs.”

In this case, the public’s interest in seeing the photos would be transparency into the activities performed by a taxpayer-funded institute. Further downstream, an informed electorate could engage with lawmakers to enact changes to the functions performed by institutes funded by their tax dollars. But the public cannot make this calculation in the dark.

The ‘risk of violence’ rationale on its face contains an uncomfortable admission: that the activities this research involved were deleterious enough to potentially result in violence and harassment. No serious, ethical person would endorse violent backlash against CNPRC or Neuralink lab workers. But the refusal to release the images speaks volumes. If the public requested images of an innocuous activity, such as a custodian mopping the floors of CNPRC, there would be no secrecy or litigation. Similarly, Neuralink conspicuously publishes images and videos of monkeys and pigs playing in their childlike enclosures, but nothing of the surgical procedure for which the animals are confined at Neuralink to begin with.

The second set of 186 images pertains to the actual research conducted on monkeys for Neuralink. Revealed in the written records of this research were details of infections, seizures, distress, and the harmful and hazardous misuse of a product called BioGlue (see page 4 here), which caused bleeding in one monkey’s brain and vomiting to the point of developing open sores in her esophagus.

In addition, these photos are of particular interest in constructing a fuller picture of what the primates endured. However, the Index notes that these images are “proprietary,” depicting research that was done using Neuralink “proprietary devices,” and are therefore the property of Neuralink. Moreover, the Index argues that “there would be a chilling impact on public-private partnerships if a private company’s proprietary, protected research was subject to disclosure simply by virtue of its relationship with a public institution.”

This is a conundrum of the public-private partnership from a public records perspective. If a publicly funded institute engages with a private entity to perform work, what entitlement do taxpayers have to know what these institutes are doing? While a given project may be commissioned and funded by a private business, the work occurs in facilities whose very existence, and whose operating costs, are largely funded by taxpayers. CNPRC receives public funding in addition to what it received from Neuralink ($14.9 million in 2021 to maintain operations , according to PETA, while the price tag for the Neuralink monkey experiments was $1.4 million).

But even if the public’s entitlement to the records was not contentious (ie. the public had a clear legal entitlement to the records), in both sets of photos, the Index argues that the public has a greater interest in the photos being withheld than it does in their disclosure. It says: “The public interest in promoting robust research and scientific progress through these public-private partnerships clearly outweighs any public interest in disclosure of these records.”

This rationale presents a false choice wherein the public disclosure of records and scientific progress are mutually exclusive. In essence, it amounts to deciding on behalf of the public what is in its best interest, which is not a task any institute or individual is equipped to do. Only individual taxpayers can do this for themselves. PCRM’s associate general counsel Deborah Dubow says the photos are “public records created with public funds, and the public deserves access to the research they paid for…UC Davis and Elon Musk should release the images immediately.”

In a statement earlier this year, UC Davis said it “fully complied with the California Public Records Act” in providing materials to PCRM, and that the “research protocols were thoroughly reviewed and approved by the campus’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).”

The Physicians Committee is expected to release a response to the Vaughn Index soon.

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.

I am paid 114 dollars per hour to perform certain internet services online. I had no idea it was feasible, but my closest friend joined and earned $27000 in just five weeks by doing sac-20 this simple task. Visit for greater information about visiting this page. Anyone may obtain this right away and begin making money online.

by following the directions on this website………………. https://dollarcareers20.netlify.app/

Incredibly wealthy men like Gates and Epstein think they can buy their way to immortality by torturing animals. It won’t work. For over one hundred years vivisectors have been trying to create animal models and failed. Experiments on animals cannot be extrapolated to humans because of differences in physiology, metabolism, genetics, biochemistry, and environment. Musk is doomed to fail like all the others but because of their desperation to live forever animals are put through the torments of hell.

These kind of experiments must be ended. Just looking at this monkeys eyes, one can see the pain and terror that he is experiencing. We must have limits to this kind of research and not lose what’s left of our humanity.