If the FDA won’t protect pregnant women & babies, whom will it protect?

Pregnant women at high-risk of delivering a baby prematurely are prescribed a drug, which they are told, will reduce their risk of a pre-term birth.

The drug is called Makena® (an injectable synthetic hormone, progestin), approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

But there’s a problem – the drug doesn’t work.

In fact, the drug label states, “There are no controlled trials demonstrating a direct clinical benefit, such as improvement in neonatal mortality and morbidity.”

What’s worse, is that the drug is likely to cause harm.

So, why hasn’t the FDA pulled the drug off the market?

Let’s rewind…

Pre-term babies are at risk of long-term neurological disability, admission to intensive care and severe morbidity and mortality in the first weeks of life, so extra days or weeks in the womb can be transformative.

In 2011, the FDA approved Makena through an ‘accelerated pathway’ which does not require a high burden of proof for safety and efficacy compared to traditional drug approvals.

The evidence presented to the FDA was based on a single trial of the drug in 2003 – the Meis study – which had a flawed design and it used a surrogate outcome (preterm delivery before 37 weeks of gestation) rather than a clinical outcome (reduced morbidity or mortality for the baby).

Adam Urato, a maternal-foetal medicine specialist at MetroWest Medical Centre, Massachusetts, has had concerns about the study from the start.

“It was such a flawed study. The randomisation failed because the placebo group had more women who had a significantly higher risk of pre-term birth than the group taking Makena, so it skewed the results in favour of the drug. They also stopped the trial early, which is known to exaggerate a drug’s benefit,” said Urato.

Even the FDA’s biostatistician agreed with Urato. The statistical review concluded;

“From a statistical perspective, the information and data submitted by the [manufacturer] do not provide convincing evidence regarding the effectiveness of [Makena] for the prevention of preterm deliveries among women with a history of at least one spontaneous preterm delivery.”

Notwithstanding, the FDA went ahead and granted the drug an accelerated approval anyway.

As a condition of that approval, the manufacturer agreed to conduct a “confirmatory trial” to corroborate the benefits of the drug – it was called the PROLONG study – but the results were a flop because Makena did not prevent pre-term births.

Urato thought it would be a slam dunk.

“When the PROLONG study failed in 2019, I thought everybody was going to say ‘okay, we’ve got to stop giving this to pregnant women’ and the response would be immediate. But here we are, almost three and a half years since the confirmatory study failed and we’ve continued to prescribe it to pregnant women,” said Urato.

The FDA did recommended that Makena be pulled off the market in October 2020, but the manufacturer did not comply, and since its FDA approval in 2011, over 310,00 women are reported to have received the drug during their pregnancy.

Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Foetal Medicine have continued to endorse the use of Makena and in the August 2021 guidelines to Obstetrician-Gynaecologists, ACOG discusses the use the drug without mentioning the FDA’s proposal to have the drug withdrawn.

Questions over safety

Proponents argue that while the benefits may not be established yet, Makena is “safe” and so, it should still be prescribed. However, as of 25 Aug 2022, the FDA database contains more than 21,000 reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from Makena such as insomnia, migraines, and stillbirths.

The drug already comes with a caution on its label — problems such as blood clots, diabetes, hypertension and depression. Makena is also known to cross the placenta and enter the foetal brain, the reproductive organs, and permeate throughout the developing foetus, although its full impact has not been fully elucidated.

Urato said patients need to be fully informed of the risks.

“When you counsel patients correctly and explain that there are short-term harms as well as unknown long-term harms, and then you balance the benefits – of which there are none – what pregnant woman is going to consent to being injected?” he said.

Drug maker won’t withdraw Makena

The manufacturer, Covis Pharma, has resisted calls to withdraw its drug saying that the study populations in the two trials (Meis and PROLONG studies) were too different and would explain the opposing results.

The company also argued that pre-term births in Black women are more common and therefore denying this population access to the drug would lead to racial inequity.

“Yes, preterm births are more common in Black women,” said Urato, “but everyone agrees that we should not inject drugs that don’t work into pregnant women. The FDA must take this drug off the market, immediately.”

Covis Pharma defends its position saying that the drug must remain on the market because “real world data” will show that Makena works, but Urato points to multiple studies in the US which have already demonstrated this to be untrue.

The FDA has now agreed to grant Covis Pharma a hearing to plead its case on 17-19 Oct 2022 and experts await to see whether the FDA will harden up and demand that Makena be withdrawn from the market once and for all.

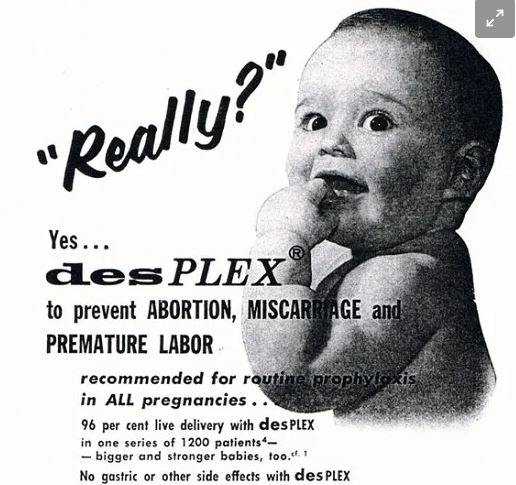

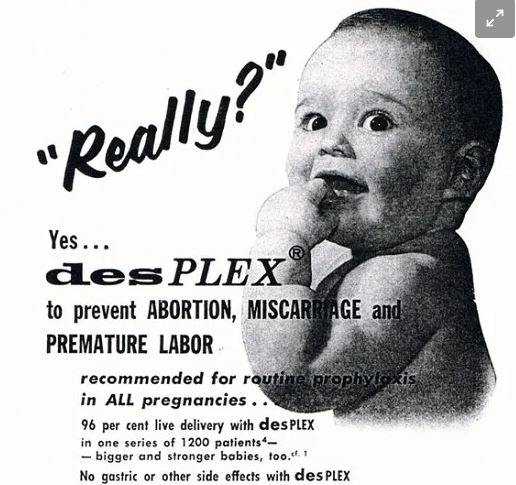

Remembering history

“We have a glaring example of getting synthetic hormones wrong in pregnancy. It’s almost as if we have just forgotten about that,” said Urato referring to the Diethylstilbestrol (DES) disaster.

DES was a synthetic hormone used by millions of pregnant women to prevent miscarriages and premature births from the late 1930s to the early 1970s.

For decades, the public was assured that DES was ‘safe and effective’ for mothers and their developing babies, but the tragedy would only unfold many years later.

The deleterious effects induced by DES were devastating; abnormalities or cancers of the genital tract and breast, neurodevelopmental alterations, and immune, pancreatic, and cardiovascular disorders.

The harms were not only evident in pregnant women but also in their children and grandchildren. Epigenetic alterations have been detected, and intergenerational effects have been observed.

In retrospect, experts should not have exposed pregnant women and their developing babies to a synthetic hormone which did not have good evidence for safety and efficacy.

“And yet here we are, 50 years on from DES, and the FDA is exposing pregnant women and their developing babies to a synthetic hormone, which does not have good evidence for safety and efficacy. If the FDA won’t protect pregnant women and babies, who will it protect?” said Urato.

In 1961, my mother-in-law was offered thalidomide for morning sickness while pregnant with my husband. She declined. Thalidomide was given to pregnant women throughout the 50’s and into the 60’s. It was responsible for terrible birth defects/