“How Frank Lloyd Wright Built America”

A uniquely American vision

Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy represents one of the most significant chapters in American architectural history.

In an era when modernism was shaping life to feel wholly inorganic, Wright went against the grain, shaping buildings to instead sit harmoniously with their surroundings.

From his spiritual connection to his home state of Wisconsin to his “organic style” innovations and final grand visions, let’s retrace Wright’s steps to becoming America’s greatest architect…

Organic Architecture

Wright’s connection to Wisconsin began with his birth there in 1867. Its rolling hills and prairies were his first architectural inspiration, influencing his later philosophy of “organic” architecture — and his quest to create a uniquely American architectural style.

Working on his uncle’s farm in Wisconsin’s Helena Valley, young Wright’s immersion in the landscape proved far more influential than any formal education. He developed an intimate grasp of the landscape’s natural patterns and how buildings can harmonize with them.

We can see how the rhythms of the land — horizontal prairie lines, limestone outcroppings, rolling hills — became embedded in his architectural consciousness in what he would later design.

How farm buildings sit naturally in the landscape, respond to the seasons, and serve both practical and aesthetic purposes became the foundation of his philosophy.

Wright’s breakthrough was to see buildings not as an imposition on the natural order, but as an organic outgrowth of it. This would later manifest in his concept of organic architecture and his lifelong commitment to buildings that are “married to the ground.”

A Clash With Modernity

Wright’s journey began in Chicago during its post-fire building boom at Adler and Sullivan — a firm at the forefront of producing Chicago’s earliest tall buildings. His drawing skills immediately caught the attention of Louis Sullivan (father of the American skyscraper), leading to his assignment on ornamental designs for the Chicago Auditorium.

Under Sullivan’s mentorship, Wright absorbed crucial principles like organic ornamentation and the relationship between form and function.

Sullivan’s famous maxim, “form follows function”, proposed that the utility of a building should be the starting point of its design — but Wright saw through its short-sightedness. Instead, he proposed:

“Form and function should be one, joined in a spiritual union”

Although he gained invaluable experience from Sullivan, Wright was driven to push beyond his mentor’s teachings early on. While employed, he even accepted secret residential commissions to supplement his income.

These “bootleg houses” in Chicago’s Oak Park reveal a fascinating transition in Wright’s development. Although these designs largely conformed to contemporary tastes, they contained the early seeds of Wright’s emerging vocabulary: extended horizontal lines, open floor plans, and natural materials.

When Sullivan discovered these projects in 1893, Wright departed the firm, beginning an independent career that would revolutionize American architecture.

Forging a Vision

Wright became best known for designing homes. His vision, to modernize American living in a way that was harmonious with nature, developed into his Prairie School style, which featured horizontal lines (echoing the Midwest prairies) and low-pitched roofs with overhanging eaves.

As a young country with vast space to expand, Wright believed there was something profoundly American about the horizontal. Sweeping roofs and horizontal lines became his touchstones, as well as open, flowing interior space, built-in furniture and lighting, and natural materials and textures.

Wright saw buildings growing naturally from the land, so materials should be used honestly and naturally, and design should respond to its environment. If that sounds vague, you can see it concretely in his later Smith House in Michigan, where organic architecture matured in his “Usonian” style. Though strikingly modern, it couldn’t be more in touch with its location.

Wright’s philosophy extended to the “destruction of the box” — the rejection of confined, box-like rooms in favor of flowing, open spaces and the integration of interior and exterior space. His career saw many technical innovations, like new heating and cooling systems, natural lighting, and novel uses of concrete and steel in residential design.

His developments came during significant social change, growing middle-class prosperity, and America’s cultural independence from European traditions.

A century on, Wright’s ideas for the optimal American home are taken for granted — but they provided the model for almost every suburban house built in post-war America.

Disaster and Rebirth

In 1911, Wright embarked on one of his most personal projects: Taliesin. Built on his ancestral land in Wisconsin, it’s where his organic architecture principle becomes most evident — positioned gracefully along the hillside rather than atop it. Wright used local limestone and wood to create harmony between structure and landscape.

Tragedy struck in 1914 when a servant set fire to Taliesin and murdered Wright’s partner (Mamah Borthwick), her two children, and four others. With remarkable resilience, Wright rebuilt Taliesin, only to see it damaged by fire again in 1925. Each reconstruction allowed Wright to refine his design principles, and the estate became his home and living laboratory.

Completing the Vision

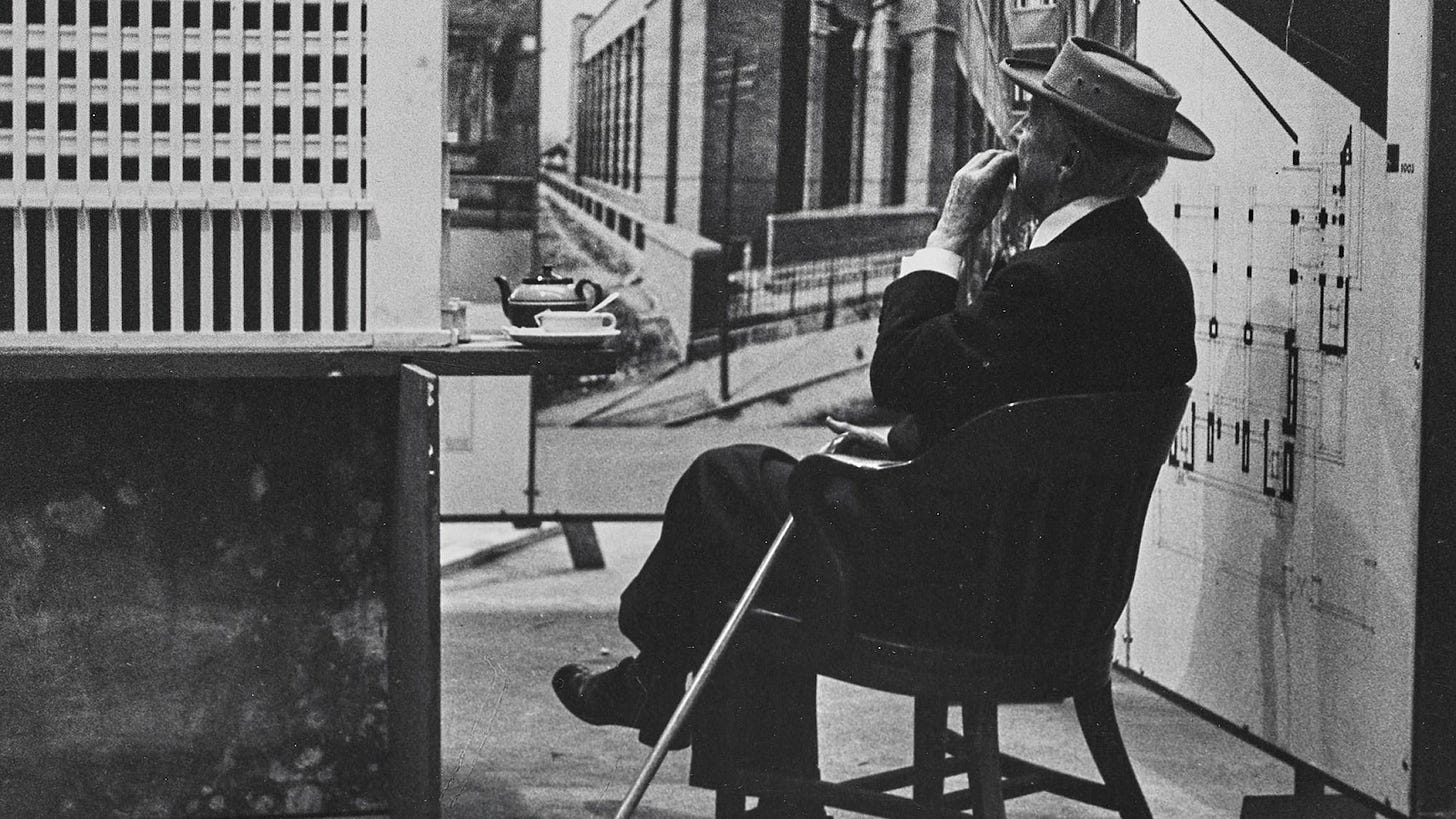

In 1938, Wright unveiled his ambitious idea for Madison’s civic center, a structure that would connect the shores of Lake Monona to the State Capitol. His dream design meant sweeping curves to echo the natural shoreline, and while it faced significant political obstacles, Wright championed his vision until his death in 1959.

In the 1980s and 90s, city leaders revived the project to adapt Wright’s design for a modern convention center. While its interiors were redesigned for contemporary needs, the exterior remained true to Wright’s dramatic curvature.

Over time, Wright’s mature style flourished across Wisconsin, most notably in the First Unitarian Society Meeting House in Madison (1951), an expression of spiritual architecture through its prow-shaped roof and manipulation of natural light.

Beyond Wisconsin’s borders, Wright’s later career produced some of his most celebrated works. Fallingwater in Pennsylvania (1935) harmonized architecture perhaps as far as is possible to imagine — an entire waterfall flows through it.

His works became wildly complex and imaginative: the earthquake-resistant Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1922) showcased his structural know-how, Oklahoma’s Price Tower (1956) explored his theories of vertical architecture, and his final work, New York’s spiraling Guggenheim Museum (1959), challenged traditional museum architecture.

A Lasting Legacy

Wright’s legacy, rooted in his love of Wisconsin’s landscape, resonates powerfully in today’s world. Integrating modern buildings with their natural surroundings established principles that seem prescient in our eco-conscious culture.

Wright’s connection to Wisconsin shaped his vision and, by extension, the course of American architecture. As contemporary architects grapple with creating environmentally responsive, socially meaningful buildings, Wright’s vision remains top of mind.

His legacy, rooted in Wisconsin soil, still grows and evolves, inspiring us to see architecture as he did — an organic expression of our relationship with the natural world.

Subscribe to DailyClout so you never miss an update!

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.