Feminists for Life Say: “Rape Survivors’ Access to the Supportive Care Act (SASCA) is a Feminist Priority”

When I experienced sexual assault after work one night, I came home not knowing what to do. The cook at the restaurant in which I worked, had been making sexual advances throughout the night, which I tried to get out of and had even told my supervisor about during my shift. She had kind of shrugged it off. At the end of the night, she asked me if I would take the cook home and I didn’t know what to say. But she was my boss, and a female I had confided in, so I thought I would be OK. Instead, later that night, on our way home, he raped me.

I arrived home four hours later than I had been expected. I was scared, angry, hurting, and tired. And during my ordeal, my roommate, Danny, had been freaking out the whole time, wondering where I was. (Cellphones were not being carried yet.)

Danny kept asking me what had happened. Like many survivors, I was in shock. So I shook him off with, “I’m fine; leave me alone.” He wouldn’t drop his questioning—he was a good friend. I finally told him what had happened, and he immediately picked up the phone and dialed a rape crisis hotline. As I said, he was a really good friend, and that was the right thing for him to do.

When the counselor came onto the phone line, it was hard for me even to speak. Things seemed unreal—I wasn’t even sure that everything that had just happened had in fact taken place. (Later I learned that this is a form of dissociation characteristic of trauma.) Anyway, I was sure that whatever had happened, was my fault. Wasn’t it?

Surprisingly, the rape crisis counselor who talked to me on the hotline, was a guy. He explained that I should consider reporting to police what happened to me. I honestly don’t really remember what else he said; no showers—something about that. I was so overwhelmed, I hung up and sat down, and as if operating on automatic pilot, I wrote my paper for my college class that was due in two hours at 8 am. It was now 6 a.m.

Danny drove me to school to drop off my paper, and insisted that we go back to the restaurant where I worked, to report what the cook had done to me. With his help, I confronted the management. They (reluctantly) called the police but only after they brought in the cook—my perpetrator—to stand in front of me. The police arrived. My perpetrator started bawling, saying he would never do anything like that. I was shocked, and I was now beyond super-scared and upset. I was only 20; he was 36. This was my part-time job, they told me, but it was his career which they said I was ruining by making this statement.

The police took me down to the station. They explained that I could press charges, and that I should, as he had a record (but it was mostly with drug trafficking). The police kept saying, “You could prevent this from happening to other women.”

And I remember thinking, “Why is that my responsibility? Isn’t that yours?”

There was so much pressure on me, and all I could really take in at that time was that everything that had happened must have been my fault. I kept replaying the moment after he was finished with me, when he slapped my face and said, “See ya ’round, b*tch.” Now, in stark contrast, he had been sobbing in front of the manager, denying the whole thing.

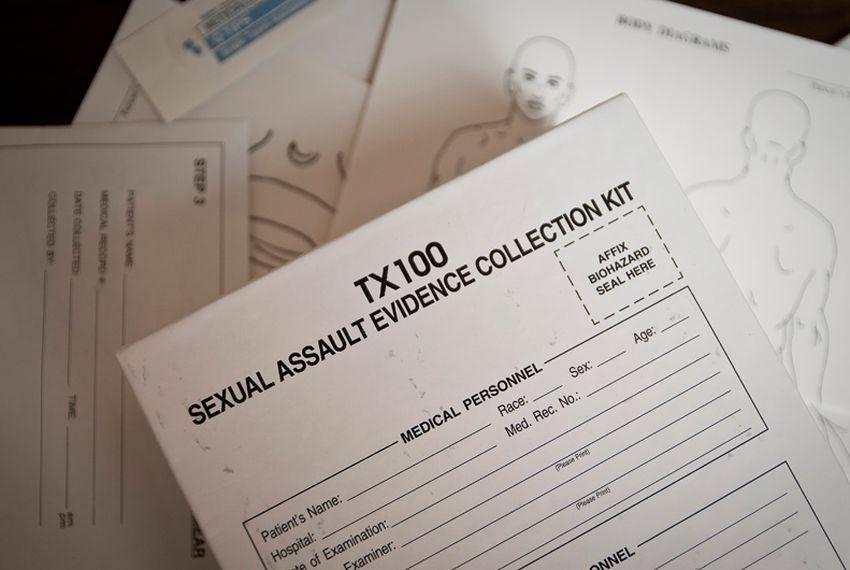

Meanwhile, as my brain whirled in a panic, the police officer was staring at me, waiting for my answer about whether I would press charges. He did say they could get a rape kit done, but he warned me that prosecution of rape is difficult. (Rape kits keep the DNA of perpetrators, by preserving swabs of semen, hair, or blood that can be used to positively identify a rapist if the kits are processed. Every unprocessed rape kit is a possible conviction that will never take place.)

But this thought was distressing. I just wanted it all to end. The thought of a rape kit, which involved an invasion of my body yet again, scared me to death. The thought of facing the cook in a courtroom scared me even more.

“No thanks,” I said and walked out.

I never went to a hospital, I wasn’t directed to by the police in case I changed my mind about prosecuting him, and I wasn’t aware of any supportive rape counseling services to seek to access. A few months later, I did go to my on-campus health center and was finally connected to some counseling.

This was all in a suburban area near a major metropolitan area. Now imagine if I were in a rural area, where the closest hospital—or any services for rape victims—is hours and hundreds of miles away.

When I read the Survivors’ Access to Supportive Care Act (SASCA), a new bipartisan bill that would create an important structure of support for survivors, it brought back all these memories.

I began to think about how my situation could have been handled differently by the police and the management of the restaurant. I don’t think anyone really understood the trauma I was experiencing and therefore, they didn’t know how to reach me and to help me to make critical informed decisions.

Many of the issues that faced me, and that face other victims, are the issues the SASCA legislation seeks to address. Its primary focus is to reach those victims in rural and tribal areas where resources are sorely lacking. It also seeks to create a national sexual assault task force and to provide funding for states to survey barriers that remain keeping survivors from getting help, and to develop a blueprint of how to address them.

Additionally, it seeks to create a much-needed national standard of care for sexual assault survivors.

SASCA enjoys bipartisan support. Introduced by Sens. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), along with Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Pete King (R-NY), the bill would allocate $2,000,000 for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2024 to improve sexual assault care, $5,000,000 for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2021 for the pilot program to train those who work with sexual assault victims and survivors, and $11,000,000 for each fiscal year from 2019 through 2024 to award grants for clinical training for counselors to help survivors.

For my part, I would be honored to assist those creating the program in any way I can.

“SASCA is a priority for pro-life feminists,” says Serrin Foster, president of Feminists for Life of America. “This is a natural next step after our work to pass the original Violence Against Women Act and the Unborn Victims of Violence Act, aka Laci and Conner’s Law, inspired by the murder of Laci Peterson while pregnant with her son Conner by her husband, Scott), and it follows our longstanding work advocating for state protection from rapists who seek custody or visitation rights. As Feminists for Life, we are not just focused on preventing abortion through resources and support—which we see from a holistic feminist perspective, as harming women—but also by supporting women in many ways that pro-choice advocates might find surprising. We at FFL have been talking about rape kits since it was a campaign issue in 2000, when I researched it and found that the rape kit processing backlog was a national issue.” Foster, who herself narrowly escaped a gang rape, asks, “Why should rape victims have to pay for evidence collection, when other victims of serious crimes do not?”

The work that Feminists for Life has done on Capitol Hill to advocate on behalf of all victims of violence—both born and unborn, and including this work on behalf of rape victims—and their allowing me to share my story as part of that advocacy, has been a huge part of my own healing journey as a survivor.

Twenty-four years after the original Violence Against Women Act, legislators have a chance to take the next steps for victims of sexual assault, especially those in areas with few resources and underserved populations. This bipartisan legislation could have a powerful effect on supporting new rape victims who are likely to be in a state of shock or trauma, and hopefully help to prevent future rapes by recidivists, because rape is a often a crime of serial predation.

We must continue to fight for survivors as we ultimately work to establish a society where sexual violence becomes unthinkable.

When you see your senators and representative at home during their August vacations, make sure you urge them to support SASCA—SB3203 in the Senate and HB6387 in the House—when they go back to work. Use the BillCam of the bill embedded here, to:

1. Contact your members of Congress

2. Post the bill to Twitter and Facebook to mobilize support

3. Alert your friends to the bill—which you can actually read and share in the BillCam.

Let them know we will be watching.