Covering President Donald Trump at CPAC

Notes From a Former Political Consultant

This is one of those “essays I fear to write.” I fear that those who are passionate admirers of President Trump will take umbrage at my notes about his recent speech at CPAC; and that those who are appalled at the mere mention of his name, will be even angrier at me than they usually are — as in this essay I treat him seriously as a Presidential candidate.

As many know, I used to be a political consultant — for President Clinton’s re-election campaign in 1996, and for Vice President Gore’s 2000 Presidential campaign.

Before I was a consultant, I was a White House spouse; my then-husband was a speechwriter for both President Clinton and for Mrs Clinton. I became familiar, from an observer’s distance, with the intense cycle of Presidential speechwriting and revision.

Then I became a consultant, and a participant in observing the speechwriting process myself.

Though I signed NDAs, and thus can’t discuss the details of my work for either campaign, I can speak generally about what I learned; about what can be helpful for a candidate for the Presidency, and about the common stumbling-blocks that face all candidates for that US office.

I also learned from both roles about the “message” process: the daunting task that a team of media specialists undertakes, of getting the press corp to cover what is actually in the speech — ideally focusing their stories on its policy centerpiece — rather than running stories that elide the speech altogether, to focus on some random “clickbait”.

(It was extraordinary to learn how often the national press corps simply does not report on the contents of a President’s or a candidate’s speeches, no matter how important, or even run a link to the transcript, but will rather run stories “about” the speech “occasion,” that are really about the audience, or a recent scandal, or a poll, or whatever the First Lady was wearing.)

For a speech by a US President or Presidential candidate to be successful — covered accurately in the media, the main points highlighted, and pushing the agenda or polls, and remembered positively by posterity — the message team must also follow certain methodologies in the production of the speech and its distribution to the press.

After that, the advance team — the people who execute the mechanics of the “Principal’s” appearance at a venue: prepare the green room; deliver the candidate physically; seat the press and VIPs; launch the music; light the stage; distribute press materials — must also take certain steps.

After all of this preparation, the candidate or the President him or herself must be disciplined in giving the speech, as a performance to a live crowd.

He or she must not yield to temptations to pander to the crowd, to extemporize in damaging ways, to go on too long in response to rapturous audience reactions, to pursue rabbit holes tangential to the momentum of the speech, or to take defensive swipes at critics.

This refusal to be tempted of course in all of these, and other, ways, and to stay, as we say, “on message”, is called, in that world, “message discipline.”

####

In my role as visiting professor of rhetoric at George Washington University, where I taught the history of advocacy rhetoric, I learned what it was that made for great public speeches in Western history.

My findings from the research I did there combined with what I learned from the other roles I mentioned and confirmed that the elements of a great public speech in the West — and a great Presidential speech or campaign speech in America — are systematic and universal.

A great public speech in the West shares certain key attributes. By the same token, Presidential or Presidential candidates’ speeches fail, no matter what the “Principal’s” background, or political orientation, is – for similar reasons.

Briefly:

1/ Great public speeches must have a clear introduction. Within the first few paragraphs, the audience must know: what is this speech about? What is the thesis statement of this speaker? As they ask in Journalism 101: “Who What Where When?”

Here is 5th century BCE Athenian statesman Pericles’ great funeral oration, per Thucydides:

“I will speak first of our ancestors, for it is right and seemly that now, when we are lamenting the dead, a tribute should be paid to their memory. There has never been a time when they did not inhabit this land, which by their valor they will have handed down from generation to generation, and we have received from them a free state. But if they were worthy of praise, still more were our fathers, who added to their inheritance, and after many a struggle transmitted to us their sons this great empire. And we ourselves assembled here today, who are still most of us in the vigor of life, have carried the work of improvement further, and have richly endowed our city with all things, so that she is sufficient for herself both in peace and war. […] But before I praise the dead, I should like to point out by what principles of action we rose ~ to power, and under what institutions and through what manner of life our empire became great. […]

Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. Our government does not copy our neighbors’, but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty an obstacle, but a man may benefit his country whatever the obscurity of his condition. […]. While we are thus unconstrained in our private business, a spirit of reverence pervades our public acts; we are prevented from doing wrong by respect for the authorities and for the laws, having a particular regard to those which are ordained for the protection of the injured as well as those unwritten laws which bring upon the transgressor of them the reprobation of the general sentiment […] Because of the greatness of our city the fruits of the whole earth flow in upon us; so that we enjoy the goods of other countries as freely as our own.”

From these two paragraphs, Pericles’ audience understood that while the occasion was funereal, the subject was Athenian democracy in relation to themselves — and its corollary, civic freedom.

By using the occasion to mourn, as an occasion also to remind Athenians that generations before them had fought to preserve their civic liberty and their rule of law, and by noting that the freedoms and public life they inherited protect and benefit them — Pericles reinforced his listeners into a civic community, with shared values of utmost importance.

That action of community reinforcement and reunification is a key purpose of a successful US Presidential speech. A great American Presidential speech should remind Americans of their story, their place in the generations, and the need for them always to re-commit, as a community, to the practice and defense of freedom.

2/ A great Presidential speech must have a clear structure. The listener must always know where he or she is, within the unfolding of the argument. This gives a speech a sense of momentum.

John F Kennedy’s inaugural address is a good example of a Presidential speech with a mappably clear structure. President Kennedy, as many know, was a devoted reader of the classics. The central premise of Pres. Kennedy’s inaugural address is that he is renewing, like Pericles, ancestral vows to defend freedom. In the center of his address he offers a serious of pledges.

The pledges have to do with foreign policy. They spell out the postwar role of the United States as the global beacon and template of liberty; they identify, though in poetic language that owes much to Pericles and other Athenian orators, a clear international policy that rewards freedom-oriented postcolonial nation-states, and threatens to deter tyrannies:

“Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This much we pledge–and more.

To those old allies whose cultural and spiritual origins we share, we pledge the loyalty of faithful friends. United there is little we cannot do in a host of cooperative ventures. Divided there is little we can do–for we dare not meet a powerful challenge at odds and split asunder.

To those new states whom we welcome to the ranks of the free, we pledge our word that one form of colonial control shall not have passed away merely to be replaced by a far more iron tyranny. We shall not always expect to find them supporting our view. But we shall always hope to find them strongly supporting their own freedom–and to remember that, in the past, those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.

To those people in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves, for whatever period is required–not because the communists may be doing it, not because we seek their votes, but because it is right. If a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich.

To our sister republics south of our border, we offer a special pledge–to convert our good words into good deeds–in a new alliance for progress–to assist free men and free governments in casting off the chains of poverty. But this peaceful revolution of hope cannot become the prey of hostile powers. Let all our neighbors know that we shall join with them to oppose aggression or subversion anywhere in the Americas. And let every other power know that this Hemisphere intends to remain the master of its own house. […]

Finally, to those nations who would make themselves our adversary, we offer not a pledge but a request: that both sides begin anew the quest for peace, before the dark powers of destruction unleashed by science engulf all humanity in planned or accidental self-destruction.”

From Kennedy’s inaugural address, usually the only remembered phrase is near the conclusion:

“In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility–I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it–and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you–ask what you can do for your country. [Italics mine]”

However, this extraordinarily memorable phrase, that four subsequent generations have used to summarize the hopeful idealism and spirit of national unity of “Camelot”, would not have been so easy to lift out, if the inaugural speech itself — which is only 1366 words long — were not so crisply structured.

3/ The successful Presidential or candidates’ speech must clearly spell out the policies proposed.

President Clinton was elected in 1992, and his early speeches were a nightmare. They were “wonky”, a word that seemed coined specifically for him and his policy team; wordy and circular and repetitive and, worst sin of all, they used insider jargon more suitable to a Columbia University economics seminar than to a speech for Americans from every walk of life.

President Clinton’s popularity was at its lowest, and his media critics were at their most effective, when his speeches had these burdens of language, because the people themselves literally could not understand what he was saying. The whiff of elitism embedded in this kind of language did not help him, either.

When people don’t understand or like a President’s speeches, it creates a media vacuum; and then scandal, rumor, gossip, sniping, and nonsense enter the void, and dominate the press’ coverage of that Presidency.

By 1996’s State of the Union address, President Clinton had become much better at speaking in plain English, and in presenting an organized policy list in simple terms.

President Clinton used the opening paragraphs of his State of the Union – the top real estate, rhetorically- to showcase indisputable statistics and concrete benchmarks:

“The state of the Union is strong. Our economy is the healthiest it has been in three decades. We have the lowest combined rates of unemployment and inflation in 27 years. We have created nearly 8 million new jobs, over a million of them in basic industries, like construction and automobiles. America is selling more cars than Japan for the first time since the 1970s. And for three years in a row, we have had a record number of new businesses started in our country.

Our leadership in the world is also strong, bringing hope for new peace. And perhaps most important, we are gaining ground in restoring our fundamental values. The crime rate, the welfare and food stamp rolls, the poverty rate and the teen pregnancy rate are all down.”

He then parsed the speech cleanly into seven “challenges”: to “strengthen America’s families”: to provide Americans with “educational opportunities”; “to help every American who is willing to work for it, achieve economic security”; “to take our streets back from crime and gangs and drugs;” “to leave our environment safe and clean for the next generation”; “to maintain America’s leadership in the fight for freedom and peace throughout the world” and lastly, “to reinvent our government and make our democracy work for” citizens.

Each “challenge” sub-headline (“subhed” in the lingo) was buttressed by his itemization of specific accomplishments of his administration – ranging from a voucher system for retraining for new jobs, to Congress banning gifts and meals from lobbyists, to the shrinking of the Federal government under his watch, to his signing an executive order to deny Federal contracts to businesses that hired illegal immigrants.

Most remembered from this speech was his “third way” approach to welfare reform:

“I say to those who are on welfare, and especially to those who have been trapped on welfare for a long time: For too long our welfare system has undermined the values of family and work, instead of supporting them. The Congress and I are near agreement on sweeping welfare reform. We agree on time limits, tough work requirements, and the toughest possible child support enforcement. But I believe we must also provide child care so that mothers who are required to go to work can do so without worrying about what is happening to their children.

I challenge this Congress to send me a bipartisan welfare reform bill that will really move people from welfare to work and do the right thing by our children. I will sign it immediately.”

Some reporters made fun of his granular approach — this itemization of his achievements and goals, down to the details of banning meals for lobbyists. Others criticized him for being policy-oriented at the expense of soaring rhetoric.

But I would say that these down-to-earth, well-structured itemizations of easy-to-understand, mainstream policy goals and results, saved his Presidency.

Because the man or woman in the street could understand President Clinton’s speeches, and thus credit his administration for working hard to get deliverables to them and their families, the precious swing voters that any candidate needs in order to win, voted him in twice; the second time with an even greater margin.

As importantly, the coverage of his speeches actually often included these easy-to-lift-out, bullet-pointed, lists of real outcomes.

These Clintonian speeches coincided, I would say not randomly, with the high points of his popularity. They gave him, in my view, some of the political capital in the bank that allowed him to survive the sexual scandal that broke the following year, and an impeachment.

4/ Finally, the greatest Presidential speeches must have clear and poetic imagery, and tell stories. President Reagan was called “The Great Communicator.” Credit for this characterization should really also go to his gifted speechwriter, Peggy Noonan. It was she who brought the uplifting, spiritually-oriented and poetic language into Reagan’s most-remembered speeches.

A beautiful example of her work is the speech that President Reagan gave upon the 1986 explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger, which killed “seven heroes”, seven male and female astronauts, on live television.

Like some of the greatest American Presidential speeches, this elegy was brief — only 648 words. (It owes a great deal to the Gettysburg Address of 1863, which in turn also owes a great deal to Pericles’ funeral oration.)

The Challenger speech, offered to a shocked and mourning nation, concluded with an unforgettable image lifted from a poem titled “High Flight” by John Gillespie Magee Jr.

‘“The crew of the space shuttle Challenger honored us by the manner in which they lived their lives. We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and “slipped the surly bonds of earth” to ``touch the face of God.”

####

Why do I recap the high points of my class on the history of rhetoric, and my findings from my consultants’ life, about what makes a great Presidential speech?

Because I watched Press Trump speak at CPAC — it was the second time I had heard him in person give a speech — and I have some perhaps unasked-for notes.

I am not partisan.

But as you know, I think our country is in dreadful trouble — I think it has already been captured. In my view, any non-globalist, nationalist candidate running in 2024 should be heard as loudly and clearly as possible, so that citizens can make the best possible choices.

President Trump is in many ways, a great speaker. The crowds that assembled to watch him in the massive ballroom of the Gaylord Hotel, were ecstatic. But there were, in my opinion, addressable problems, and real missed opportunities, in his speech.

First of all, it is difficult for me, as a reporter trying to cover the speech, to tell you what he said in terms of the “meat” of it, the substance.

He came onto the stage, after pounding pop and country hits had energized the audience, looking fit and well; he wore his signature navy blue suit with boxy shoulders, white shirt and red tie. His hair was more grey than red-blond; he looked less like a “celebrity,” and more “Presidential”. The crowd was screaming with joy.

But if I were his consultant, I would have observed that crowd’s ecstasy with mixed satisfaction and alarm. His live audiences’ impact on his own delivery style and his choices onstage, is not necessarily good for his outcomes this Fall.

President Trump spoke scathingly about the failures of the Biden administration — the poverty and homelessness in our cities, crime and lawlessness, and the open border. He vividly painted, mostly extemporaneously, a picture of the ruin and degradation in just four years of a once-great nation.

However, when he turned to his own plans for his second administration, he was far less specific. He essentially said at one point that his main policy objective for his next administration was to “Make America Great Again”.

This got a roar of approval from the audience. But it was not answer enough, I argue, for the undecided or swing voter, or for the homeless former Democrat.

President Trump was very clear on some of his themes and plans, but quite vague or rhetorical when it came to others.

He was very strong on his past achievements, and his future plans, in terms of foreign policy. He told again the story (and it is a satisfying story) of how he had used the threat of tariffs, to get Mexico to provide military security at our Southern border. He was extremely detailed and specific about how he will close the borders, and deport the illegal aliens who have entered our nation by the millions. But even with the discussion of foreign policy, his language was often anecdotal and personal, with almost no analysis: he presented a series of meetings with “tough” leaders, who reacted well to his own “toughness.”

Swing or undecided voters are in anguish about our environmental problems. But President Trump merely gestured at the environment — wanting to make America “beautiful” again — with almost no specifics.

He claimed a strong economy in his past administration, and promised a strong economy in the future, but it is difficult to recall his specific policy proposals to achieve this.

Unfortunately, in between what were far too few concrete descriptions of his past achievements for our nation — which I had learned only by looking them up directly earlier, had, to my surprise, been considerable — he often committed the kinds of rhetorical lapses that would give thoughtful, experienced advisors, high blood pressure.

He digressed.

Oh, how he digressed!

Some of his digressions were hilarious — for instance, he brilliantly told a self-deprecating story about landing in Air Force One, in Iraq, in a state of anxiety, in total darkness. It was fall-on-the-floor funny. It got peals of laughter.

But there he left it. He had said earlier in the speech that he had started no new wars — which could be highlighted as a huge deliverable, appealing to all voters — but he did not tie this anecdote to that larger point. Indeed he tied that story to no larger point at all about Iraq, or about fear, or about conflict.

If he had had a tough speech editor, the editor would have red-pencilled the anecdote: “What point are you making here? Conclusion needed.”

President Trump took swipes at the obvious dementia of President Biden — that were, again, meanly funny, and that got big laughs.

But he could have made that same point more sadly and gently. He could have thus gotten the votes of all those who worry about President Biden’s mental state, and also added all those who are caring for a loved one with dementia — not a small voter category. I registered, listening as a journalist, that those moments would be lifted out by the media, to portray him negatively.

He told hilarious anecdote after hilarious anecdote. The problem is that the live audience loved him. His live audiences always adore him. That is not news. The CPAC crowd cherished the personal stories, the improv, the humor.

But there are some problems with this speech style, for the rest of us.

One issue is that such speeches guarantee poor press coverage.

I, as a member of the press, watched nearly half an hour of his time go to hilarious anecdotes, repetitions, mean swipes, and charming jokes, in such a chaotic and circular way that, as I noted above, it is very difficult indeed for me to write an article pinpointing what exactly his speech was about.

The circularity, digressions and repetitions also prevented the speech from having the “liftoff” that a great speech delivers — that sense of moving with the speaker through time, to arrive at a new destination.

If I were an advisor of his (and I am not angling for a job; just imagining his staff’s tasks in handling him), I would be gritting my teeth at the half hour of digressions, because they took up so much room that there was no systematic summary by the end of his time, of what he had achieved for the country during his first four years, nor a clear projection of what he would do for us in the next four years.

As noted, when the press can’t easily lift out the bullet points of a speech, they fill the space under deadline with mean quotes, gossip, scandal, invective; and what President Trump calls “fake news.”

But why needlessly give them the opportunity to do this?

President Trump is not the only candidate whose best talents can be killed or diverted or suffocated with undue responsiveness to live-audience love.

President Clinton had similar faults — both were or are so good with live audiences that they seduce and are seduced by the live audience, leaving the press and the viewers at home, who may not be so in love with the candidate, often bored or restless or unmoved.

I watched the reaction of the press corps around me, and observed my own internal responses.

A meme that circulated later on social media — a snapshot of a reporter playing a digital card game while covering President Trump’s speech at CPAC – seemed to those who were sharing it like a criticism of the reporter in question.

But speaking as a neutral observer, and as a reporter, it’s actually a criticism of the candidate.

A great speech, or even just a substantive speech, will rivet any audience member, even if he or she is politically opposed, or neutral.

During various flights of Trump-ness that led the live audience into paroxysms of adoration, I felt the same sense of detachment as did the reporter who was playing digital Hearts.

Why?

Because President Trump seemed to be speaking only to those who were already besotted, not making his case to the rest of America.

The live audience at CPAC is not everyone. President Trump forgot, I felt, that he was speaking not just to his base, but potentially to millions of undecided Americans who were watching at home.

All candidate can fall into the trap of mirroring only the concerns and language of their bases, and forget that most of the country has to vote for you, if you are to win.

Many phrases that President Trump used at CPAC were right perhaps just for his base, but wrong for a general audience. For instance, he did little to distinguish legal from illegal immigrants, which vagueness allowed the press inaccurately to call him “anti-immigrant.”

Candidates for President in the past only became President when they solved this problem, of moving from their appeal to the base, which population alone can never get you elected or even outdo the cheating margins, to an appeal to the moderate middle.

An example of this evolution was when President Clinton moved from the language of “welfare” to “welfare reform.” Or when Candidate Bush II said, about abortion, “good people can disagree.”

The best and most influential speeches of Presidents Lincoln, Kennedy, Reagan, Clinton, and Bush II, appealed to the “us” in Americans, and were inclusive, not narrowly partisan.

There was another moment in which I thought President Trump burned political capital needlessly. He pointed directly at the media seated — he literally pointed his index finger at us far in the back of the ballroom, and at the video and TV cameras too — and said that the “fake media” were “corrupt.”

Not “some” in the media. Not “many” in the media. But “the fake media.”

Why do this? Certainly the legacy media have been and are usually corrupt in covering President Trump. I acknowledge this in my essay “Dear Conservatives, I apologize. “

That moment of attacking the press, which I believe is repeated in other speeches of President Trump’s, was pure red meat for the crowd. They howled with joy.

But if I were advising President Trump I would warn him against the temptation of catering to that live reaction.

What if there were a few reporters in that ballroom who were open to writing positive or at least neutral stories about the speech? I was seated in the group that had the accusing finger pointed at us from the stage. It was an unpleasant experience and it felt unjust.

Not every reporter is corrupt. Also, power balances can shift in the course of a campaign, and an editor who has commissioned nothing but hit pieces in the past, can shift to neutral or positive stories when the polls evolve. But the polls won’t evolve much, and nasty coverage won’t change, if President Trump continues so flamboyantly to make a wholesale enemy out of all of the press as a category.

Lastly there were some miscalculations, in my view, by his advance team. One is that, as I mentioned, the press corps was seated at the far rear of the ballroom. It felt stigmatizing to be seated further away from the candidate than anyone else.

Other campaigns seat the press up front or at the sides of the stage, or even on the floor at the foot of the stage. This proximity has many advantages. One is that when photographers are seated at the foot of the stage, they are forced to shoot with their camera lenses angled upward. This angle reproduces a longstanding visual convention in art history, and now in politics, that portrays someone as heroic. If photographers are seated far away, rather than at the foot of the stage, they take level photographs and video of the candidate:

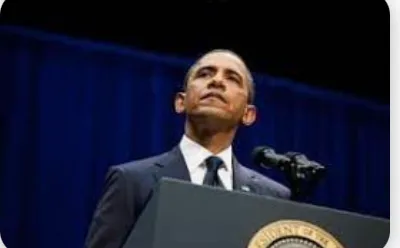

Compare the above to President Obama’s imagery, and President Clinton’s, whose staffers forced photographers to shoot upward from beneath the podium:

This “heroic angle” actually derives from classical imagery of leaders — notice that “heroes” are always on plinths or on horseback?

(This “heroic angle” has been exploited by fascists, communists and leaders of free societies, alike.)

Aesthetics aside, there were other omissions that prevented positive or even substantive coverage of Pres. Trump’s CPAC speech.

Our advance teams, back into 1990s, would give press kits to all media present, with a speech summary clearly presented, and the bullet points and key quotes already lifted out. This gave reporters no excuse not to report what was in the speech. At CPAC there was no such summary or bullet-pointed press kit distributed to us — to my knowledge at least — so a reporter heading back to his or her hotel would be forced to rely on wading through a transcript, re-watching the speech and taking notes (incredibly slow and laborious when one is on deadline), or else be driven to simply recycle: again —- gossip, innuendo, slander, and some quote from a random purported Nazi at CPAC, if one could be found.

My view of press coverage is that the subject always has a responsibility at least to make it easy for the press to understand what was said. If the press has that summary in hand and then smears or mis-reports the speech, that is fully on them. But if one leaves gaps such in press outreach, one bears some responsibility for poor or nonexistent or “fake news” coverage of a candidate or a speech.

And indeed the reports of the CPAC speech were full of “fake news.”

Rolling Stones’ headline was: “Self-Proclaimed ‘Dissident’ Trump Rails on Newsom; Calls Migrants’ Languages a “Horrible Thing.”

This is Rolling Stones’ summary of the speech:

“The hour-and-a-half rambling speech covered Trump’s typical gamut, where he touted his cognitive abilities while demeaning President Biden’s; defended Jan. 6 insurrectionists; ripped on the media; and preached a doomsday scenario if he is not reelected. He compared migrants to Hannibal Lecter, claiming “they are terrorists” who are “killing our people,” and a “contagion” — echoing his previous Hitler-like “poison the blood” rhetoric.”

Would you vote for someone who did all of this? Most Americans would not.

So, the CPAC speech itself is misrepresented grossly by this Rolling Stone summary. But also, it isn’t.

Unfortunately, Press. Trump was indeed so loose and anecdotal so often in his detours and riffs, that these words could indeed be lifted out of the verbal spaghetti on the plate, and presented thus damagingly out of context. And it is difficult to find a transcript online, so the legacy media is free to distort what he said, as they have.

Why not say “many” or “some” illegal immigrants are “terrorists?” Why not say “many” or “some” in the media are “corrupt”? I was there, listening as President Trump did his jazz-extemporaneous riff on the many languages of the illegal immigrants.

I knew when he said “It’s a horrible thing” that he was talking about the entire scenario that preceded that statement: the invasions, the crimes, the lawlessness. But my reporter brain recognized the “Bingo” moment: I knew that other reporters would lift out the phrase “It’s a horrible thing” and relate it just to the preceding sentences about foreign languages being spoken. And I knew with what aversion swing or undecided voters would hear that.

Why make these careless lapses in specificity, which are so easy for a hostile press to exploit?

Why, by not giving the press a tight printed speech with bullet points and summary, and by not training the candidate to stay on message, pave the way for President Trump’s critics to dismiss him as “rambling”?

Why, why, if you support this candidate’s policies, make it so easy for his critics to smear him entirely?

I am in the sad position of having seen President Trump twice, and having been impressed, wholly against my will, by much of what he had to say.

Most of the rest of the country has not had that experience; their knowledge of him is filtered through this hostile media.

He can win if he and his team prioritize message discipline, structure and good advance work. His adoring base will send me angry emails now no doubt — “We love him just the way he is, because he is real”. “He does not talk like politicians — that is why we love him.”

I am sure that that is true, but the rest of the country is not so all-embracing.

And any good candidate, with his or her speechwriter, can attain a healthy balance: offering structure, and adding flights of seeming (but carefully vetted) improvisation, that do not get the candidate in trouble again and again with the press and with undecided voters. There is a way to improvise so that vagueness and rhetorical lapses do not drown out the overall very important policy message.

I guess what I am saying is that President Trump’s speeches and speaking style do not do justice to his record of achievements, and actually sometimes undermine many people’s ability to understand and evaluate his record.

President Trump — indeed any nationalist candidate running for US President in 2024 — should take a careful look back at the great speeches of the past, including the great American Presidential speeches.

These candidates should, in my humble view, rein in their human inclinations to respond primarily to the swooning responses of their live audiences and their devoted bases.

They should remember that the great and successful US Presidential candidates, and indeed the great US Presidents, spoke with focus and discipline and strength and a sense of mission. And they did all of this by addressing the “better angels” of our nation as a whole; and by issuing historic and a future-oriented calls to duty and unity — to all of the American people.

Originally published on Substack.

Additional reference: https://sambaslots.org/sv/

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.

From Naomi’s descriptions of his speech, it sounds like President Trump thought he was delivering a monologue for Comedy Central. 😉

And it light of stunts like the one described in the article below, what business did Trump have speaking at the “Conservative” Political Action Conference anyway? 😛

https://www.lifesitenews.com/blogs/playing-with-fire-donald-trump-welcomed-a-homosexual-wedding-at-his-mar-a-lago-resort-home/?utm_source=featured-news&utm_campaign=usa