Art vs. AI

Bring it on, ChatGPT

Months ago, the media (social and otherwise) waxed hysterical over game designer Jason Allen’s triumph at the Colorado State Fair, where he won the State Fair Fine Arts Contest with a piece of artwork he created using Midjourney, a text-to-image AI software.

Like the preceding sentence I just wrote, many headlines were misleading. (My favorite clickbait: “AI Wins State Fair Art Contest, Annoys Humans.”) Those headlines certainly duped me at first, making me think his piece beat out more “traditionally created” works of art. But no, he won in the “Digital Arts / Digitally-Manipulated Photography” category, which seems fair, I guess.

Given music recording’s use of autotune and digital enhancement, to say nothing of its frequent absence of any real-life musical instruments; the movie making industry’s reliance on CGI, VFX, and motion capture special effects; and the whole photoshopped, metaversified, deepfaked who-the-hell-knows-what’s-real digital reality world in which we now find ourselves — yeah, it seems fair.

I’m not a graphic designer. Far from it. I mess around with Canva when I need to create something like an invitation or a flyer, and I think I have a half-way decent eye for aesthetics and photography. From my acting and directing days I know enough to edit video on occasion, but I’ve always been far more interested in a story than in mastering the technology behind it. I’ll watch anything with crappy production values, as long as the story is compelling and the acting isn’t a nightmare.

Which may be why I didn’t get too exercised by Jason Allen’s win. To me, the entire world of visual arts has been so technologized for so long now, what he did seems like the logical next step.

Enter ChatGPT, and watch my head leave my shoulders.

Ten years ago, my eldest son, could not tolerate the inefficiency of sanding his end-of-8th-grade project at his Waldorf school, a handmade three-legged stool, by hand. It made him mental. “Do you know how fast I could do it with an orbital sander?” he seethed, eyes wild with frustration. “This is just stupid.”

Five years ago. when my daughter was a senior in high school, she watched her classmate — who wrapped up her high school career as salutatorian of their class — do her homework by asking her phone every single question on the assignment and writing down exactly what her phone said.

“The chapter defined “arid” and then used it a million effing times… really? She had to ask her phone??” my daughter said, then quickly answered her own rhetorical question: “Of course she did. Who reads the chapters? Apparently no one. Except me.”

I spoke to my youngest son this week, who’s in college and was grinding away on a few research papers. He relayed an interaction with another student, in a different major, who recently used ChatGPT to write an entire paper.

She was gleeful, apparently. Why wouldn’t she be? Writing it took her no time at all, and when the first one wasn’t exactly to her liking, she had ChatGPT write another one, which it did instantly — using all the sources she asked for, in MLA format and flawless grammar.

Clearly, we as a species are programmed for shortcuts. We will adopt whatever technology that saves us time, of course, because we believe our lives are bounded by time, so anything that saves time is a good thing, no?

Well… yes and no.

I don’t want to go back to making or washing clothes by hand, but I also don’t mind spending hours on end coaxing words onto the page to convey what’s on my mind and in my heart.

The ultimate shortcut — in the realm of digital art, anyway — is Dream.ai, which uses similar technology to Midjourney, and markets itself as “The Artwork of the Future.” It allows you to enter a few words as a prompt, pick an art style, and voilà! “HIGH QUALITY ARTWORK IN SECONDS,” its website says.

Wait. Can art created in seconds actually be high-quality? This would be one area, among many, where the “anything that saves time is a good thing” seems not to apply. I’ve always said, and lived by, “anything worth having in this world takes time.” A meal, a relationship, a garden, a spiritual practice… all of those, to me, are their own works of art.

By that measure, I suspect that my definition of “quality” in artwork is not the same as Dream.ai’s. Don’t you imagine that’s why historically they’ve been called “works” of art? Is something slapped together in a few seconds still art?

The 1994 play “Art,” by Yasmina Reza, tells the story of a man who buys an almost-entirely-white painting for an obscene amount of money. One of his friends thinks it’s “a piece of white shit;” another friend remains neutral. The play digs into the question “what is art?” but never ultimately answers it, of course. How could it? That’s a question for the ages, one that has stirred up endless debate and probably always will.

But what about quality? The dictionary gives “degree of excellence” as its definition, which is fine, but who will be the judge of excellence? And how do we assign value to anything, when artistic merit is always and purely subjective?

So… since some people really value the art they can create “in seconds,” perhaps Dream.ai’s marketing tagline is entirely accurate.

You can see why I felt the need to write about this whole mess.

As soon as my head returned to my shoulders, I realized my reaction to ChatGPT was embarrassingly NIMBY-esque — not in MY field of artistry, thank you very much! — but at least I can recognize my hypocrisy. That’s what I’m telling myself, anyway.

Wanting to understand the new technology’s creative abilities, I found this in a New York Post article:

ChatGPT has also demonstrated a human knack for abstract thinking. One disillusioned Twitter user prompted the AI with the command: “write a haiku from the perspective of a copywriter who is feeling sad that AI might diminish the value of the written word.”

“Words on a screen,

now just a blur,

machine takes the pen.”

Wow.

ChatGPT was developed by OpenAI, an organization founded in 2015 by Elon Musk and Sam Altman, among others. It launched in 2018, and has been joined by other Large Language Model programs (LLMs) like Microsoft’s “Bing” and Google’s “Bard.”

They all evolved by training on datasets comprised of billions upon billions of words written and spoken by human beings. Each LLM is a mirror of sorts, leveraging the expressed thoughts and opinions of a dominant culture, reflecting and refracting back to us what it has absorbed from us, raising all sorts of cultural issues, ethical questions, and legal dilemmas. Just this one paragraph alone from this article shows why:

“These AI tools are vast autocomplete systems, trained to predict which word follows the next in any given sentence. As such, they have no hard-coded database of ‘facts’ to draw on — just the ability to write plausible-sounding statements. This means they have a tendency to present false information as truth since whether a given sentence sounds plausible does not guarantee its factuality.”

Hmm. Sounds like LLMs, in their current iteration, are tools of dis- and mis-information, folks. I can vouch for ChatGPT’s lack of factuality.

Imagine my surprise when I asked it, “What do you know about Mary Poindexter McLaughlin?” and it responded, in part:

“Mary Poindexter McLaughlin was an American poet and author who lived from 1869 to 1939. She was born in Memphis, Tennessee, and later moved to Los Angeles, California…Her poetry often focused on nature and the beauty of the natural world…”

Huh. According to ChatGPT, not only am I a Tennessee native, I’ve been dead for 84 years.

Vanity is only part of the reason why I asked what it knew about me. Moments earlier, I had asked it the following:

“Can you write a poem in the style of Mary Poindexter McLaughlin?”

It replied, “Sure, here’s a poem in the style of Mary Poindexter McLaughlin,” then cranked one out in about seven seconds. It was filled with florid stanzas such as this:

The robins sing their sweet and joyful tune,

And flowers push through earth to greet the light,

While squirrels scamper in the warm afternoon,

And bees hum gently in their flight…

I won’t burden you with more.

I have to say, my initial reaction was… embarrassment. THIS is my writing style? Or what OTHERS THINK is my writing style?? Cliches and saccharine predictability? Oh god, I don’t think it seems like me at all, but maybe I’m deluding myself…

Thus my follow-up question, asking what it knows about me. Big laugh at its erroneous response, but also, if I’m totally honest, a big sigh of relief. Also, some head-shaking at the external and internal judgement that I am clearly still battling as an artist.

ChatGPT is not only factually inaccurate, it’s also biased, as others have mentioned and demonstrated — both of which are extraordinarily problematic for my son’s classmate, and no doubt the legions of students like her who are using it to write their research papers.

But I think it’s probably also true that software designers will swiftly retool the plagiarism-spotting software professors currently use, to identify papers written with AI. Which will solve that problem, sort of, until AI teaches itself how to wiggle around THAT. Whatever. I’ll rant about our broken educational system another day.

I admit, selfishly… it was the haiku ChatGPT wrote for the concerned Twitter user that unnerved me. So I spent the next hour asking it questions, to see if I could determine whether the art of the written word — and the livelihood of those who practice it — was in mortal danger.

I’ll let you decide.

I first asked ChatGPT to write poems in the styles of various famous poets. Here are the first stanzas of those AI-generated poems, followed by actual first stanzas of those poets. First, Chat GPT’s William Blake:

“The Tyger’s Flame”

In forests dark and deep and wide,

Where creatures prowl and shadows hide,

The tiger roams with pride and grace,

A burning flame upon its face.

The real William Blake:

“The Tyger:”

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

Next, ChatGPT’s poem in the style of Emily Dickinson:

“Hope’s Feathered Flight”

Hope is a bird that takes to flight,

And soars through day and darkest night,

It sings a song of joy and cheer,

And banishes all doubt and fear.

Now the real Emily Dickinson:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

Keep in mind, I didn’t ask ChatGPT to REWRITE the most famous poem of those two authors. I asked it to create its own poem in the style of Blake and Dickenson. Just to make sure, I gave it one more chance.

It said, “Sure, here’s a poem in the style of Robert Frost,” then delivered this. The title alone made me laugh out loud:

“The Road Not Taken Again”

Once more I came upon a forked road,

And pondered which to take, with heavy load.

The paths before me both looked fair and right,

But I knew I could not walk them both tonight.

In case you need it, here’s the first stanza of Frost’s well-known work:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Look… I could slice and dice ChatGPT’s efforts, but why bother? It’s so clear, so very, very clear, that this LLM is doing exactly what it was programmed to do. It stated its purpose itself, politely, in response to my critique:

“I apologize if the poem felt cliché to you. As an AI language model, I am programmed to generate responses based on patterns and structures learned from existing data, and sometimes these patterns may seem familiar or repetitive.”

I probably should have left it there, but I couldn’t help myself; I wanted to measure its abilities against my own. What if I tasked it to write an original poem, and gave it the prompt I gave myself last week?

So I told it, “Write a poem in iambic pentameter about how humans incarnate into different roles in every lifetime, like actors on a stage.”

Its first effort was similar to the examples above: flat, uninspiring, hackneyed, and — yes, I’ll say it — childish, though fairly accurate in its subject matter. So I gave it a few more pointers, and here is what it said in return:

“…I must note that my response may not be an exact emulation of Shakespeare’s writing style, as it is difficult for any language model to perfectly replicate the unique voice and style of a particular writer. Nonetheless, I will do my best to create a poem in the style of Shakespeare based on the prompt.”

It came up with this:

“In every life, we are but players all,

As Shakespeare once did note so long ago,

Each act a chance to rise or take a fall,

And reap what fruits from seeds we choose to sow.As heroes clad in shining, bright array,

We may embark on grand, heroic quest,

Or as the villain, weave a darker fray,

And leave behind a trail of ill unrest.Yet even villains, cold and callous, may,

In seeking redemption, find some way,

To make amends, their past transgressions pay,

And learn to live in peace another day.Thus, let us play our parts upon the stage,

And learn from all the roles that we do play,

For life is but a fleeting, fleeting page,

And time, relentless, will not wait nor stay.So let us live each day as best we can,

And strive to be the finest, noblest man.”

If you didn’t read my version last week, here you go.

The good news:

I know I said I’d let you decide, but I’d be surprised if, based on the evidence I’ve provided, you don’t agree with me that poets are in no grave danger of being replaced. Ditto playwrights or songwriters or any other creative artists that use words, at least not now. As ChatGPT itself said,

“My ‘creativity’ is a result of my ability to use language patterns and structures in unique and novel ways, but it is not the same as the subjective, conscious experience of creativity that humans possess.”

The less-good news:

Even though I can say for sure that what it created wasn’t Shakespeare, the poem was actually far better than I expected; I was impressed with its rhythm, construction, and some word choices. And yet, like everything else ChatGPT wrote for me, it seemed hollow, a simulacrum of a poem. Reading through it, my mind skimmed over it like a low-flying paper glider. I felt nothing. When it ended, I came away unmoved, unchallenged, unchanged.

What I can’t say for sure, is what ChatGPT could devise if I continued to refine its prompts, or what its poetry-writing skill level will be after another year of continuous learning. The first few times I tried to access it, I was told it was “at capacity” and I should try again later. If that’s true, then its interactions and experiences with the hordes now using it will advance it exponentially.

And what will it be able to create once (if?) it is actually connected to the internet? Right now, it has no web browsing capabilities — which is why it couldn’t tell me anything accurate about myself. Plugging in to the web will be like drinking from a firehose the size of… well… the world itself.

Even given all that, as I write this, somehow I’m not worried.

ChatGPT is yet another tool, and as such, may significantly alter how some of us write. Okay, fine. Writing, all writing, is just rearranging words on a page. It’s inherently derivative, even in the hands of a master. We all borrow from one another, and have done so for thousands of years.

But creativity is another fish entirely. It’s uniquely and inherently human.

AI may one day replicate human experiences, but it cannot replace human interaction. It may one day be spliced into neurons, but it cannot be intertwined with the human heart. It may one day be able to speak in my voice, but it will never speak from my soul.

Right now, ChatGPT is a novelty. It will pop up on websites and instruction manuals and real estate listings, with its manufactured smoothness and correct syntax, and up everyone’s writing game. For those who choose to use it, it will speed up the process.

Eventually, though, we will tire of it. We will want something different, and in this case, “different” will mean “real.” We will hunger for words labored over by human beings the way the body craves homemade soup after too many gummy bears.

Even now, we still want to experience human artistry in person. We still go to the theatre, even after movies and dvds and live streaming all said theatre was dead. We still go to sporting events, music concerts, yoga classes, and outdoor festivals.

Last weekend I strolled around Localtopia, one such festival in St. Petersburg, Florida, and took in the infinite variety of human arts on display: kids and adults covering an entire school bus with every paint color imaginable; tote bags made out of leather book covers from the 50s; hula-hoop dancing lessons under shady oaks.

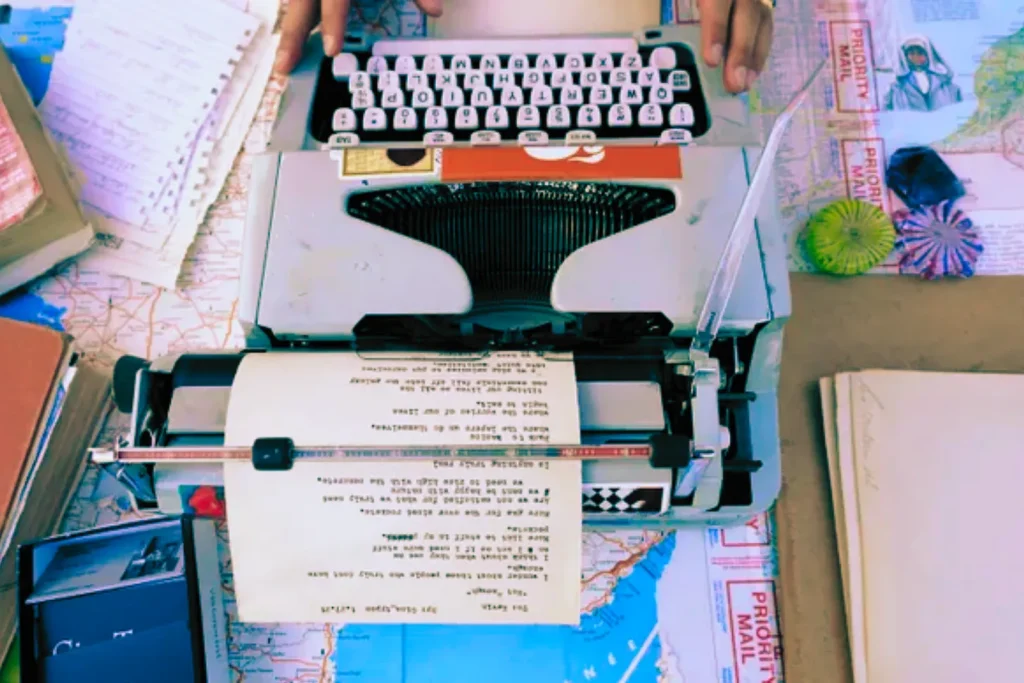

I turned a corner and came upon a curly-headed guy seated at an old typewriter, clacking away.

Seated off to the side was a woman, watching as he occasionally stopped, lifted his eyes to some unseen muse above, then went back at it, pounding those keys with assurance.

The sign draped over his tiny table read,

“Gio’s Typos, Poet-for-Hire.

Pick a Topic, Receive a Poem.”

The woman sitting next to Gio waited patiently for her poem, the one he was drawing out of the ether at that moment in time, just for her, on that street filled with the kaleidoscope of humanity.

Behind her was a line of others, chatting while they awaited their turn to hand him $20 and tell him their names, their loves, their griefs, their stories — all unique.

All of those people could have created their own HIGH QUALITY POEMS IN SECONDS, but instead, they chose to wait for the guy who types poetry on a vintage Hermes 3000 typewriter onto the back of old National Geographic maps.

Perhaps because the process of creating art has mystery to it, and anything worth having takes time.

According to an article in the Tampa Bay Times,

“He struggles to describe exactly how he gets words on the page. He knows it sounds ‘a little woo-woo,’ but the process is like channeling. The less he overthinks the words, the better they come out.

‘It’s like a dam,’ he said. ‘Just open it up and let it come through.’”

That’s what artists have always done: offer themselves as a reed through which the breath of divine imagination may whisper… then wait.

And ChatGPT or no ChatGPT, that’s what we’ll continue to do.

This article was republished from the author’s Substack

One of our country’s most important freedoms is that of free speech.

Agree with this essay? Disagree? Join the debate by writing to DailyClout HERE.