Thou Knowest Not: Flaws in the World of Medicine Revealed

Consider a simple game. It involves two people, Marie and Jose, standing several feet apart. Jose faces Marie and imagines a large tic-tac-toe pattern two feet in front of her face. He reaches his hand into one of the imagined squares and snaps his fingers. Marie, eyes closed and stationary, reaches to find Jose’s snapping fingers.

Most of us in Marie’s role can play this game fairly well. We would sense the general direction of the sound. Our first reach for the snapping fingers may not be perfect, but we’d usually be in the ballpark.

That’s because our brains map sound. Our brains are made for three-dimensional processing. They track sound in three-dimensional space. Imagine if your brain could not do that, could not process sound spatially.

Imagine if your brain also struggled to process space itself. Visualize yourself in a room walking toward the door. Your brain processes the space of the room; it processes the narrowing space of the approaching doorway; and it processes the widening space on the door’s other side. Your brain is constantly doing geometry, innumerable three-dimensional computations with each step.

But what if your experience of space was unstable, with visual scenes bending like a virtual reality of Einstein’s General Theory? What if the doorway was there, but the space on the other side appeared warped or fragmented? As you approach the door, you hesitate. Half step forward, half step back. Forward and back again, but not through the door. Your friend in the hall calls “Come on,” but the sound comes from nowhere. You can’t map it.

This is not science fiction. I wish it were.

Indulge me a bit further. Consider the gravity receptors in your inner ears. They message the brain to recalibrate your equilibrium untold times per minute. Imagine the impairment of these, too. Your brain searches for equilibrium in vain. You tilt and waver, bending at the knee like a surfer. You walk like you’re tipsy, reaching for walls and even the floor, until that too begins to move. All the while, your brain’s unrequited pursuit of equilibrium is draining it, like a phone searching for weak Wi-Fi.

Then someone asks what is 5 x 5 + 8. You can’t quite do it. Your brain tries to compute, but is shutting down. Its struggle to process sound, space, and gravity is depleting its resources. Worse still, you now have toothbrush in hand. In the moments before adding paste, your brain stopped processing. Standing before the sink, you forget what to do. Or, conversely, your brain might run like a daemon program perpetually processing. It processes the intent of eating the sandwich. Ten minutes later, it’s still processing that intent while searching in vain for the ingested food, gesturing to the plate with crumbs in frustration – “It was right there!”

Protracted time with specialists in major cities and elsewhere yielded one unspoken certainty – knowledge about head trauma and concussion is meager.

The pretense to knowledge is vast. Only one credentialed voice confessed the inadequate state of medical understanding. Clarity would not be forthcoming for why my loved one suffered – week after week, month after month, and now counted in years. The pain of the process drowned out that candid but discomforting voice. Self-deception was easier, and more consoling: Embrace the pretense on offer most everywhere, the façade of certainty accompanied with programs and promises of recovery.

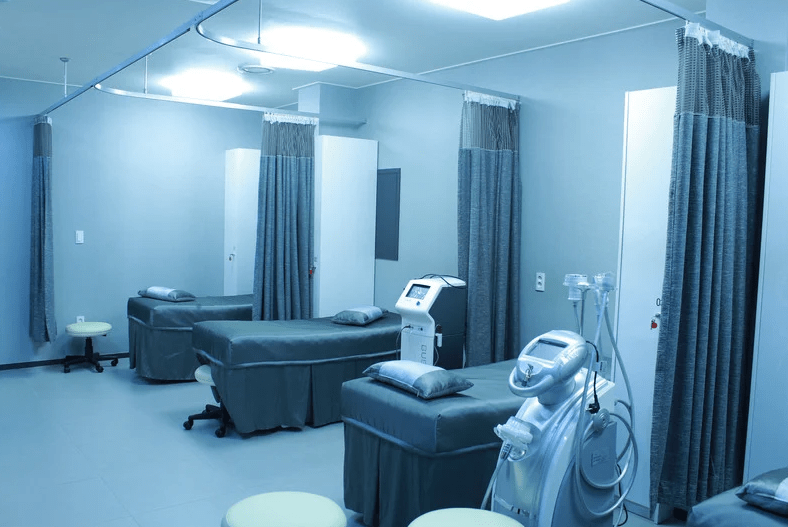

Promises are alluring. They all had price tags, but the passing of time brings desperation, and vulnerability, a readiness for the purchase of hope.

Many promises yielded little, save innuendo regarding the patient. Human nature is such that the doing of good generates probabilities of misfeasance. Mental health is so important. Spreading awareness and curtailing stigma are genuine achievements. Yet they occasion opportunities for mistreatment. Call it the moral ambiguity of the human condition. The pretense to knowledge is fortified by the sophisticated misuse of mental health nomenclature – a guise for when inadequate knowledge proves inadequate, and remittance remains due.

Some promises actually did harm. Rehabilitation can exacerbate things before the full scope of head and neck trauma is known – fistulas, dehiscences, dysautonomia, misalignments, cervicogenic dizziness, etc., etc.

There are, no doubt, many wonderful medical professionals. I’ve been fortunate to receive my share of their trained and compassionate care. I remember names from decades ago.

Yet maybe one measure of the health of our culture is how well we correlate years of education with degrees of humility. The one tempers the authority beget by the other.

The title page of John Locke’s famous Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) includes an epigraph which begins, “Thou knowest not . . .” Philosophers from David Hume to Richard Rorty have more than redoubled these limits on knowledge. And yet we have professions whose manners and modes of expression imply near omniscience. Public ambitions foster these habits. The R’s and the D’s all talk to us as if they’re all knowing, alluring and beguiling at once. We’re always tempted to purchase the pretense, to invest in the promise, depending on the letter attending the name, like vulnerable patients comforted by the air of assurance.

The era of COVID enhanced the allure of this dissembling certitude. It magnified our need for assurance and, with it, our embrace of the angst projected from podiums and platforms. Decades of messaging about the transformation-requiring invisible dangers pervading our lives prepared us for this era. States of mind about hidden forces have defined cultural status for some time – from the near apocalyptic-causing invisible compound exhaled with each breath to the unconscious carrying and transmission of micro social afflictions. Sophistication in each case was synonymous with heightened anxiety and social control. The COVID era built on these foundations. It vastly expanded the dominion of public ambitions by fostering a politics of health predicated on the administration of vulnerability. We all became patients comforted by the air of credentialed assurance. Even as “safe and effective” began to bear a familial resemblance to “shock and awe,” it remained comforting to embrace the pretense on offer, the façade of certainty accompanied with promises of recovery.

The COVID era magnified professional pretensions as it inflicted untold psychological, financial, and physical harm.

“I don’t know,” imagine public health authorities on the stage replying into the cameras in a declaration of cultural sobriety. Ruminations on the fate of these figures would commence thenceforth.

“I don’t know.” The phrase now resounds in my mind as if ensconced in a permanent niche. I profess it in the classroom more than before, especially when petitioned for certain kinds of commentary. It can be liberating in a sense. Not to pursue the pretense. Or feel the need to. Sharing and cultivating knowledge is gratifying. More than thirty years of reading, writing, and teaching history afford ample occasions. But abundant limits remain on knowledge ten times that. Sensitivity to those limits pays dividends, important yields for the classroom and culture.