“The Real-Life Fairytale Castle”

A modern fairytale with a tragic ending…

The world’s most stunning castle doesn’t come from the age of knights. It’s the product of one man’s extraordinary imagination, built to keep the wonder of the medieval era alive in the modern age.

Neuschwanstein Castle is as stunning as a movie set — and, shockingly, it’s less than 200 years old. Nevertheless, it’s no set piece. It’s a very real castle that stands balanced between the modern and middle ages, a monument to Germany’s national awakening and to the eccentric King Ludwig who dreamed it up.

Here’s what it has to teach us about staying rooted in the beauty of bygone eras — and the dangers of getting lost in them.

The Fairytale King

Born in 1845, Bavaria’s King Ludwig II suffered a lonely childhood. The sensitive young prince shrunk from his father’s harsh discipline and retreated into the world of his intense imagination, where he immersed himself in stories, art, and music.

Reluctantly ascending the throne of Bavaria at age 18, Ludwig II faced a challenge unlike any of his predecessors: the Germanic states, including Bavaria, were coming together to form a single country, and the outside world was caught up in the fever pitch of industrialization. At the same time as it industrialized, the nascent nation of Germany was tasked with forging a national identity.

Ludwig’s artistic temperament rose to this challenge. He dedicated himself to Germany’s culture, helping her rediscover her medieval past through music and art.

His father wanted him to be a hard-nosed ruler, but in this he had no interest. He set his mind instead to constructing castles and acting as a patron to artists (like the composer Richard Wagner) who celebrated Germany’s natural beauty and epic stories. His eccentric passion for romantic epics earned him the title of “Fairytale King,” a title he lived up to with his greatest creation, Neuschwanstein Castle.

Neuschwanstein Castle

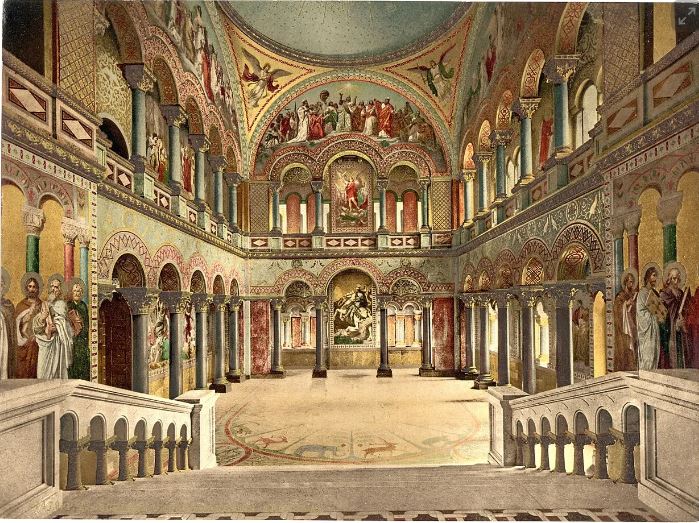

Though Ludwig built several castles, his palace at Neuschwanstein (literally, “New Swan Stone”) was truly worthy of a fairytale. Not only is it remarkably designed exteriorly, taking advantage of Bavaria’s most stunning views, but the interior is even more exquisite — a fantasia of beautiful paintings and stunning feats of architectural imagination.

Ludwig’s castle drew inspiration from medieval German palaces, Norse and Germanic mythology, and even Byzantine design. He covered the walls with scenes from Wagner’s operas and the legends that inspired them, including Lohengrin, Parzifal, and the Holy Grail.

One of the castle’s most stunning features is an artificial cave, a grotto in which the Ludwig could take refuge from the pressures of royal life and find solace in the natural world. Complete with an artificial waterfall, this of course takes inspiration from another German folk legend, that of Tannhäuser (also immortalized by Wagner in his opera of the same name).

While Ludwig seemed to stand against the industrial age, he also innovated technological changes in Bavaria. He built Neuschwanstein with central heating, an electric bell system for servants, and even automatic flush toilets.

In many ways, Neuschwanstein Castle exemplifies the best of culture: it engages the imagination and connects visitors with the best that past eras have to offer, while simultaneously integrating the most useful advancements of contemporary life.

A Dreamer’s Downfall

Ludwig’s huge expenditures on architecture and art emptied the royal treasury. Citing insanity, the ruler’s ministers deposed him in 1886 and had him imprisoned. Whether the king was truly mad or simply inconveniently eccentric has never been settled, but the greater mystery is his death: the day after his imprisonment, Ludwig’s body was discovered floating in a nearby lake.

Though officially ruled a suicide, many of the strange circumstances surrounding his death put this theory into question: not only was there no water in Ludwig’s lungs, but the body of his physician was found floating next to him. Additionally, Ludwig was known to be a strong swimmer, and the water he supposedly drowned in was no more than waist-deep. We’ll let you draw your own conclusions…

The Fairytale King is quoted to have said: “I wish to remain an eternal enigma to myself and to others.”

Perhaps unknowingly, Ludwig fulfilled this romantic ideal perhaps more than any other, with his death as completely as with his life.

Romanticism and Realism

Although he never lived to see his castle fully complete, Ludwig’s eccentric romanticism preserved Germany’s culture amidst the industrial revolution. As a creative designer, he showed how to integrate the glory of past eras with the best of modernity.

More than that, Ludwig shaped worldwide culture to this day: his Neuschwanstein Castle inspired more than one of Disney’s animated fairy tales. Disney, in turn, brought fairy tales back into the mainstream, reminding the world of the romantic stories that comprise our past.

However, striving for the ideal isn’t the only task of culture: we’re also responsible for acknowledging the demands and shortcomings of real life. While Ludwig’s luminous creativity built inspiring castles, his financial illiteracy threatened everything he made.

Creativity creates, but practicality protects the works that define our culture — and without a healthy balance between the two, the most glorious works of art can be lost.

Art of the Week

Ludwig thrived on the epic works of his close friend Richard Wagner. Their shared passion for thrilling romances and poetry helped to anchor Germany’s cultural identity.

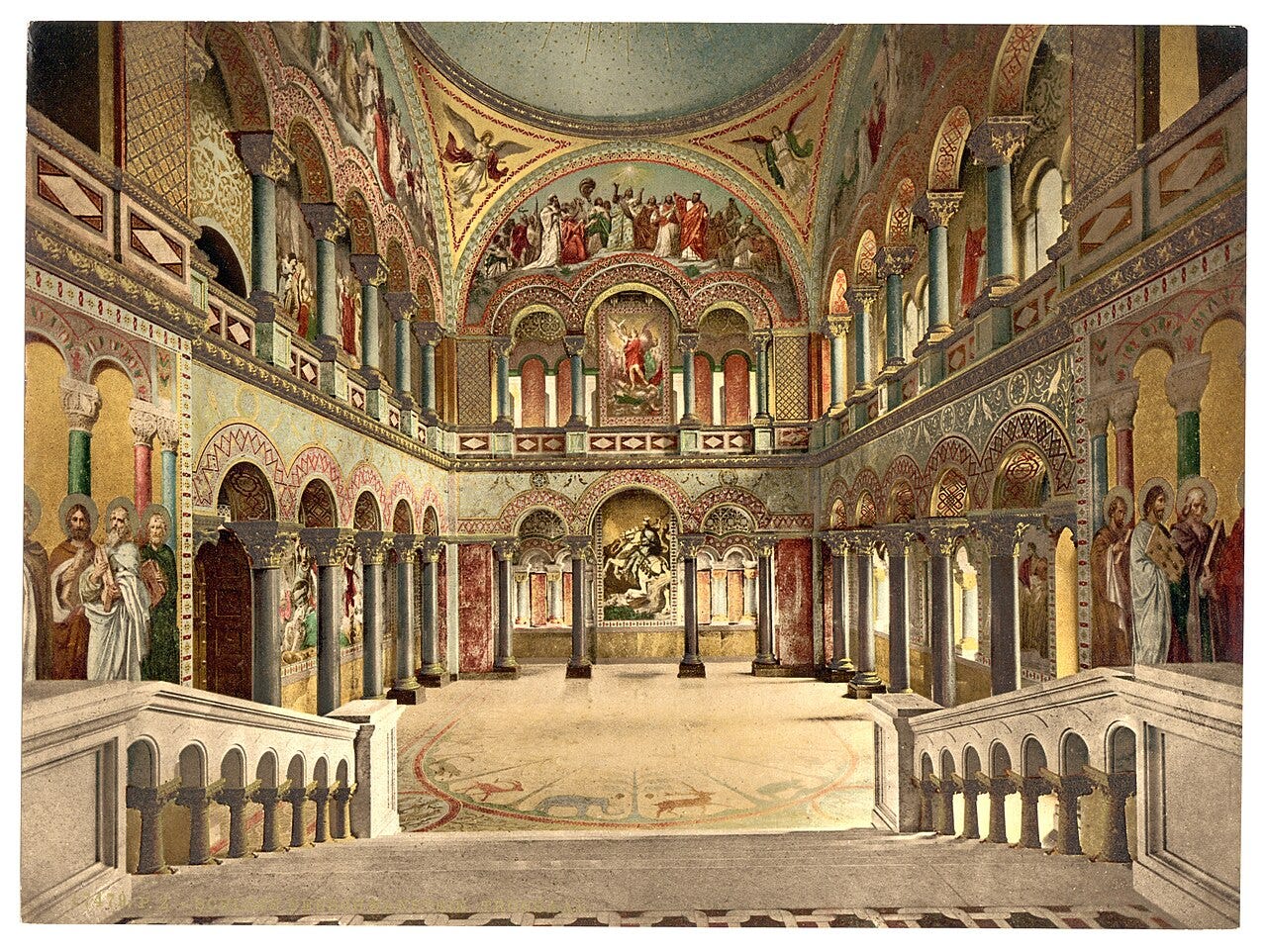

The Tannhäuser myth was one piece of folklore that inspired the duo, and ultimately led Wagner to compose Tannhäuser, a tragic opera about love, sin, and failed (or not?) redemption.

In the story, the Minnesinger (essentially a German troubadour) Tannhäuser discovers the Venusberg, the underground abode of Venus. He stays there for a year worshiping her, before he eventually realizes the error of his ways and travels to Rome to seek forgiveness from the Pope. While the real plot is much more complex than that, the story itself is a reflection on the nature of profane and sacred love, and showcases the Wagnerian ideal of redemption through the latter.

The painting in question was produced by the British Pre-Raphaelite artist John Collier, and depicts Tannhäuser at the beginning of his journey, bowing down to Venus. The Minnesinger will eventually be saved from Venus’s abode by the Virgin Mary, and find salvation thanks to the love of a mortal woman — but the path to getting there will be anything but easy…