“The Native Title Act is a Real Threat to Preventing Climate Change”

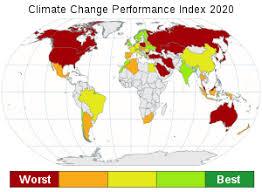

The dominant cause of climate change is greenhouse emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and coal. The wellbeing and health of people is negatively impacted from air and water pollution. Legislation in Alaska and Australia has failed to protect the right to land ownership of the Indigenous people of the land. In effect the legislation was designed to extinguish Native Alaskan and Indigenous Australians” claim to Native Title. Thus, allowing corporations and government to profit from oil and gas exploration, with no concern for the damage to health, environment, or climate.

The extinguishment of Native Title in the Galilee Basin, making way for the Adani Coal mine will notably impede the health of millions not only in Australia. But, throughout the world. (https://www.dea.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DEA-Adani-Long-Fact-Sheet_final.pdf). Furthermore, extinguishment of Native Title is not unique to Australia. Alaska was granted Statehood in 1959, becoming the State with the largest areas and longest coastline (https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/ak_statehood.asp). The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 extinguished Native Title, placing Native Alaskans in jeopardy of not only their community lands but also subsistence hunting grounds and livelihoods. Providing tentative approval of over 103 million acres of select lands to which conditional leases and sales could be made (https://www.doi.gov/ocl/hr-244). Their fears were realised, with oil and gas exploration starting on the Northern Slopes of Alaska. Including, the construction of the Trans-Alaska pipeline system (https://ancsaregional.com/about-ancsa/). The Trump administration has given the green-light to oil and gas leasing projects on the Alaskan coastline, threatening polar bears and wildlife (https://nypost.com/2020/08/18/us-approves-oil-gas-leasing-plan-for-alaska-wildlife-refuge/).

This essay will discuss the impacts on health, environment, and climate, caused by the extinguishment of Native Title claims of Indigenous Australians and their connection to country. Through their relationship and connection with the land, Indigenous peoples have developed strategies to cope with climate change. Sustainable production and consumption systems, and their effective stewardship over the world’s biodiversity, enable many Indigenous communities to live carbon-neutral or carbon-negative lifestyles. Indigenous peoples are more susceptible to these impacts as they generally live on lands particularly vulnerable to climate change, such as polar regions and small low-lying islands subject to thawing and sea level rise respectively; depend directly on their lands and waters for basic needs (shelter, food, medicines, etc.) and their cultural and spiritual identities; and experience poverty and social exclusion that heightens other vulnerabilities. Worldwide, Indigenous peoples have already experienced reduced rainfall, severe drought, higher temperatures. (Newcastle Law Review, Vol 14).

As coastal and island communities confront rising sea levels, and inland areas become hotter and drier, indigenous people are at risk of further economic marginalisation, as well as potential dislocation from and exploitation of their traditional lands, waters and natural resources,” said Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner Tom Calma.. Climate change will further marginalise Australia’s Aboriginal communities, forcing them out of their traditional lands, destroying their culture and significantly affecting their access to water resources and poses a major threat to the physical health of Indigenous communities and their ability to sustain our traditional life, languages, cultures and knowledge. In different ways, they both point to the need for Australia’s climate change response to protect fundamental human rights, especially the rights of the most vulnerable. The United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues has stated that Indigenous peoples have the smallest ecological footprints of the world’s communities and should not be asked to carry the ‘heavier burden of adjusting to climate change ’(Calma, T. and Commissioner, T.S.I.S.J., 2008. Native title report 2007. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission).

The Torres Strait, home to the group of Islanders from Mer who first won recognition of native title, with Eddie (Koiki) Mabo initiating the ground-breaking land rights case, now live with an uncertain future, urgent action is required to address. If not, they face the very real possibility of a human rights crisis and have expressed their concerns about the impact of climate change on their natural environment, visible through: increased erosion, strong winds, increasing storm frequency and rising sea levels not seen before resulting from increased greenhouse gas emissions. Forecast, greenhouse emissions from the proposed Adani coal mine will cause disastrous coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. The natural seabed will have to make way to a new coal terminal and will be destroyed by the ploughing of a million-plus cubic metres of sea floor (https://www.marineconservation.org.au/stop-adani-wrecking-our-reef/).

After repeated calls to the Australian government to reduce its’ greenhouse gas emissions and phase out thermal coal, responsible for rising sea levels. A group of traditional owners from the Torres Strait have made a watershed complaint at the United Nations against the Australian Government inaction on climate change, threatening their rights to culture and life (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-30/torres-strait-islanders-fight-government-over-climate-change/12714644).

Kevin Smith, an official with Queensland South Native Title Services Limited, has said the native title system is in need of reform as it contains convoluted, ill-fitting legislative functions and complicated and unfair claim processes, particularly in light of the heavy burden of proof, and it has been bedevilled by policy myopia. Native title has been intentionally excluded from the range of options to address underlying indigenous disadvantage” (http://www.ipsnews.net/2009/05/australia-climate-change-further-threat-to-aboriginals/).

Following the Northern Territory lifting its’ ban on fracking, Traditional landowners who, are opposed to fracking were locked out of a Origin Energy meeting. They have legitimate concerns, open evaporation ponds used will flood and flow toxic wastewater onto their land and polluting their water supply (https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2020/10/20/traditional-owners-say-origin-has-silenced-them-fracking-nt). A The Scientific Inquiry into Hydraulic Fracturing in the Northern Territory Background and Issues Paper found that arsenic, selenium, strontium and total dissolved solids (TDS) exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s Drinking Water Maximum Contaminant Limit (MCL) in privately owned water wells within 3 km of active natural gas wells.

The failure of the Native Title Act lies in the design of the legislation and its’ purpose. Which is to allow oil and gas exploration to continue on Indigenous owned land.