Sources: Wealthy Founder of Nonprofit Housing Migrant Children Asks Staff for Money

This article originally appeared in TYT Network and has been reprinted with permission.

Roughly two weeks ago, Antar Davidson’s superiors at a Tucson, Arizona, shelter operated by Southwest Key Programs called an all-staff meeting. The founder and CEO of the nonprofit corporation, Juan Sanchez, had arrived, and he wanted to address his employees.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services pays Sanchez’s nonprofit hundreds of millions of dollars a year—including $316 million since September—to shelter and transport undocumented children. For Southwest Key’s 2016 fiscal year, it reported “30,156 unaccompanied immigrant children served.”

But Davidson says Sanchez told employees that some undocumented children aren’t able to receive certain medical treatments. One child “had acne on his face an inch thick,” Sanchez said, according to Davidson, a youth care worker who no longer works at Southwest Key. The child “was so ashamed he wouldn’t look at people . . . I felt so bad that we couldn’t offer him any help,” said Sanchez, in Davidson’s account of the meeting.

Sanchez concluded by asking, could anyone join the “employee giveback program” and spare $240 for a fund to help children with extreme medical problems? Davidson said it was not clear whether Sanchez was discussing only medical care, or other forms of assistance, as well.

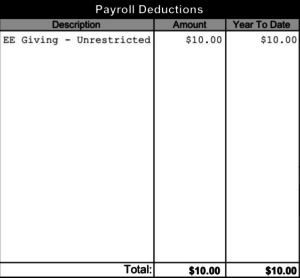

Sanchez left, and then supervisors passed around sign-up sheets for workers to commit to donating. A one-time $240 payment or a $10 deduction from each biweekly paycheck would suffice. Southwest Key Communications Director Cindy Casares denied the existence of an employee-funded program to subsidize medical care, but neither confirmed nor denied any request by Sanchez for employee donations. A “medical fundraising” operation is “absolutely not true,” she told TYT in an email. The federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, she said, “pays for the medical care of the children in our [Unaccompanied Minor] shelters and Southwest Key has no reason to fundraise for it.”

Southwest Key told the Los Angeles Times that employee donations were intended to fund a scholarship program for children who “want to further education or have extreme health or life problems.”

“It was horrible,” Davidson said of the meeting. “They were pushing it on everyone, like ‘You should sign, you should sign, you should sign.’ . . . When I saw that, I was like, ‘Ok, I don’t think the problem is just this facility; I’m pretty sure the problem is the organization.’ . . . That was kind of like the beginning of the end for me.”

“They give us the money, and then we just give it right back to them? It was very strange to me that that would happen.” Davidson said he made $15.22 per hour as a seasonal youth care worker, without benefits. Youth care workers and case managers are often non-staff: seasonal employees without benefits.

A male case manager at a different Southwest Key shelter in Arizona, who wished to remain anonymous because he feared losing his job, talked with TYT and gave an account of a similar meeting that echoed Davidson’s story. The case manager said that his meeting also made employees feel pressured to donate. “It seemed like everyone there was pretty thrown by it, even people who have been there for a while,” he said.

Nonetheless, the case manager said, he contributed. “Personally, I didn’t mind donating, because I adore these kids, and I want better services available to them,” he told TYT. “I just hope that that’s what the money’s being used for.”

The case manager estimated that one-half to three-quarters of the staff at his shelter signed up to contribute. It’s not clear whether Sanchez held such meetings at every Southwest Key facility, but the case manager told TYT he had reason to believe that the CEO visited all Arizona shelters. The nonprofit operates 27 shelters in Arizona, California, and Texas.

The case manager also said that the children do get proper health care at his shelter. “We have excellent staff,” he said. Told that Southwest Key denied the medical fund claim, he said, “Maybe the funds are to help the kids in lots of different ways, not just medical.”

A page on the Southwest Key website encouraging employee giving is no longer live, but an archived version from October 2017 includes a form for workers to sign up for payroll deductions “to support Southwest Key’s innovative programming,” signed, “Dr. Juan J. Sánchez, El Presidente and CEO.” The page says the donations are tax deductible and asks that checks be made out to Southwest Key.

Another archived page, from July 2014, asks employees to contribute to a capital campaign to expand Southwest Key’s physical facilities.

The new requests for donations come from a CEO who made almost $1.5 million last year. Sanchez’s government-funded salary has risen enormously in recent years, tracking with Southwest Key’s increased HHS contracts.

TYT reported last week that Southwest Key executive salaries increased as HHS grants and contracts did the same. From Southwest Key’s FY 2015 (September 2015 through August 2016) to FY 2016, government funding for the nonprofit rose from roughly $197 million to $323 million—a 64 percent increase.

Sanchez’s compensation increased similarly around the same time. In FY 2015, he earned $786,822 in total compensation. Then, from July 2016 through June 2017, he earned $1,477,001 in total compensation, including $398,753 in “bonus and incentive compensation,” according to an affiliated charter school’s FY 2016 tax records. FY 2016 tax records are not yet available for Southwest Key.

Cacares, the Southwest Key spokesperson, told TYT that it “is appropriate for the CEO of a nonprofit the size of Southwest Key” to have a $1.5 million salary. “Dr. Sanchez makes on the lower end of the pay scale as compared with CEOs of other nonprofits our size and as compared with CEOs at other nonprofits that provide the kinds of services that we do.”

According to Charity Navigator, CEOs of nonprofits in the human services sector and offering youth development, shelter and crisis services, and with $13.5 million or more in expenses averaged salaries of $265,000 per year. Southwest Key had $226 million in expenses in its 2015 fiscal year. A Charity Navigator study using 2014 data shows that nonprofit CEOs of organizations this size made less on average than Sanchez made during that time.

Sanchez isn’t the only member of his family to score significant compensation from the U.S. government through Southwest Key. His wife, Vice President of Community Engagement Jennifer Sanchez, earned $280,819 in the 2015 fiscal year, according to Southwest Key tax records.

Davidson said that “very few” fellow employees were aware of how much money their CEO made, and when he told coworkers, “they were shocked.”

“Honestly, I think that’s kind of gross,” said the case manager. “The employees, especially the youth care workers, they’re barely making ends meet. They have families, you know?”

Southwest Key is the same nonprofit that operates the Brownsville, Texas, shelter that barred entry to Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) when he visited on June 3. The nonprofit stated that only people approved by HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement, even members of Congress, may visit these shelters. HHS says its policy requires 14 days’ notice for any visitor.

ORR says it’s currently funding shelters to house about 11,000 undocumented children, with roughly half residing in Southwest Key facilities.

Davidson says he resigned from Southwest Key “as a conscientious objector” on June 12 after being instructed to tell Brazilian immigrant siblings “to separate.” Davidson, whose father is a Brazilian immigrant, speaks Portuguese and communicated with Brazilian immigrants in HHS custody. He taught Capoeira and English classes to the children along with the normal requirements of his job.

Davidson said that his shelter often asked its workers to work overtime, and sometimes six days per week. The case manager said that most employees are seasonal and don’t receive benefits. Because of the influx of migrant children, Southwest Key is making more jobs permanent and, therefore, providing benefits to those employees, he said.

The case manager said, “Honestly, it’s a great job, and I feel lucky that I get to be a positive part of these kids’ lives. . . . The issue [employees have] is with the policy changes and maybe pay, lack of overtime, stuff like that.”

“We truly do everything we can for the well-being of these kids,” he said.

The HHS Administration for Children and Families, which operates the Office of Refugee Resettlement, did not respond to TYT’s request for comment on nonprofit compensation, fundraising from workers, and potential uncovered medical care.